Visual Processing and Autism: Bottom-Up Processing Explained

Understanding how students with autism process visual information can help teachers and pediatric therapists better support learning and participation. A recent research article published in the Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders (Huang et al., 2025) explored how visual processing and autism are connected, specifically how autistic individuals handle local details versus the overall big picture. The findings highlight important differences in brain activity that can influence how students with autism see, interpret, and respond to their environment.

What the Researchers Studied

The study, Local and Global Visual Processing in Autism: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Neuroimaging Studies, analyzed brain imaging data from 15 studies involving over 500 participants.

Researchers compared how autistic and non-autistic individuals performed on visual tasks that measured two types of processing:

- Local processing: focusing on small details, such as finding a hidden shape within a complex picture.

- Global processing: integrating multiple details to recognize the big picture like seeing the full pattern or understanding how parts connect.

The goal was to see whether people with autism rely on different brain regions when completing these tasks and what this might reveal about how they process visual information.

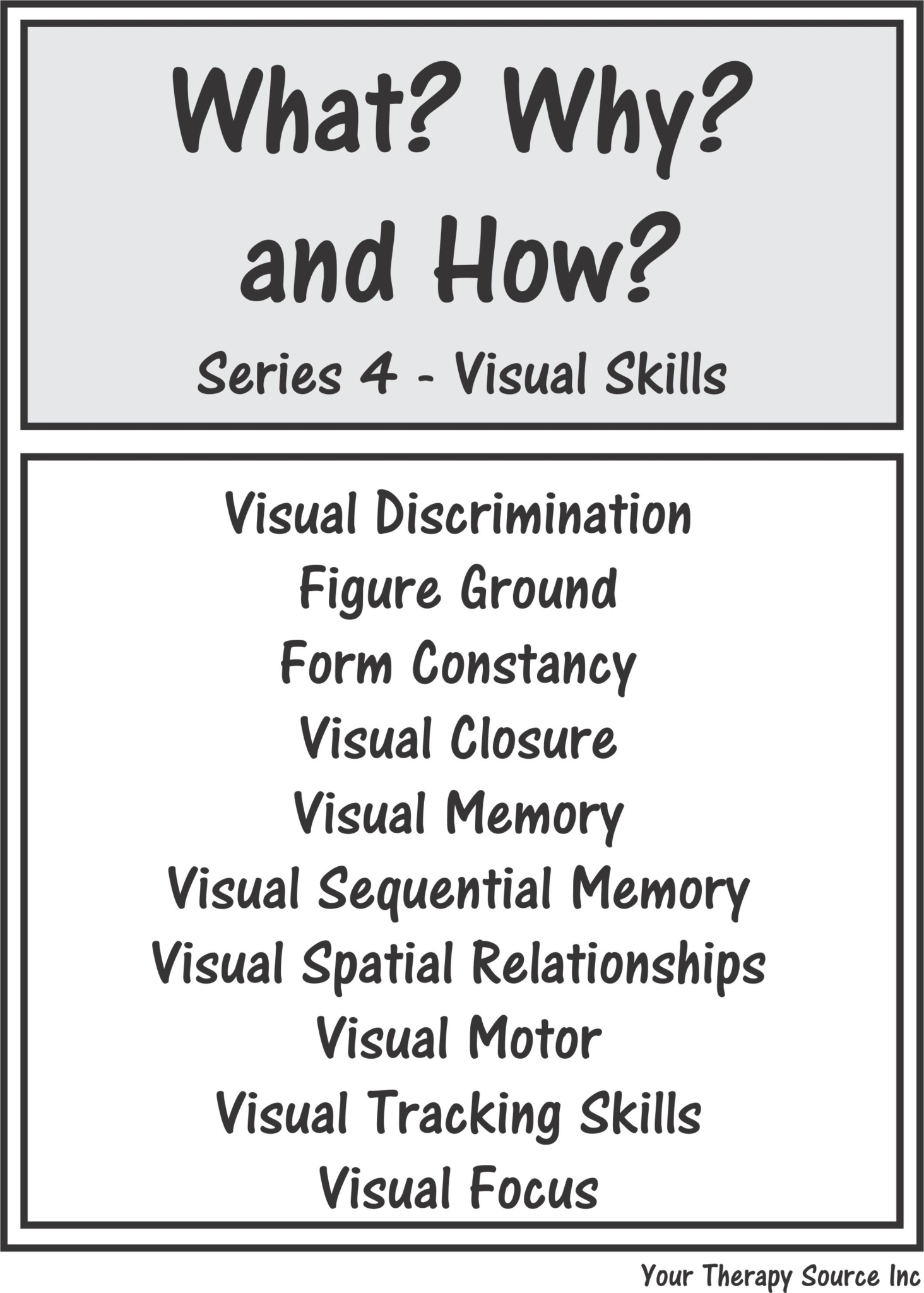

What? Why? and How? Series 4 – Visual Skills

Key Findings About Visual Processing and Autism

The study found consistent differences in brain activation patterns between autistic and non-autistic individuals:

- Autistic participants showed greater activity in the visual cortex, especially in the right inferior occipital gyrus (Brodmann Area 19), which handles detailed visual input.

- Non-autistic participants showed more activation in the parietal lobe, which integrates sensory information and helps form an overall picture.

- Task performance was often similar between both groups meaning that while autistic individuals used different brain pathways, they completed visual tasks just as effectively.

This means that differences in visual processing and autism are not about ability but rather about approach. The autistic brain may rely more on sensory-driven pathways that focus on details, while non-autistic brains may rely more on top-down integration.

Understanding Bottom-Up Sensory Processing

The research team interpreted these results through the concept of bottom-up sensory processing.

- Bottom-up processing begins with raw sensory input, what we see, hear, or feel, and builds upward toward understanding.

- Top-down processing starts with context, experience, or prior knowledge using prediction and meaning to interpret sensory input.

For students with autism, the brain may rely more on bottom-up processing, meaning sensory details take priority before context or prediction. Each piece of visual information, color, brightness, or movement, is processed fully, which can make the world rich in detail but also overwhelming.

This aligns with predictive coding models in autism research, which suggest that autistic individuals use less “filtering” from past experiences and instead process each sensory moment as new.

Category Games for Kids – Interactive and Print Versions

Why This Matters for Educators and Therapists

Understanding how visual processing and autism interact helps professionals design more supportive environments for learning and participation.

What the Research Suggests

- Autistic individuals may excel at noticing patterns, visual details, and small differences.

- They might find it more difficult to see connections or understand how multiple steps or details fit together.

- Sensory input may be experienced more intensely, making busy visual environments harder to navigate.

By understanding these brain-based differences, educators and therapists can adjust their teaching and intervention strategies to reduce stress and build on strengths.

Practical Ways to Support Global Processing

Here are simple ways to help students connect details to the big picture:

1. Use Visual Organization Activities

Provide worksheets that group related images or words (e.g., “things in the kitchen,” “classroom supplies”).

Why it helps: Strengthens connections between details and overall categories.

2. Try Step-by-Step Sequencing Tasks

Use visual or motor sequencing (e.g., brushing teeth, making a sandwich).

Why it helps: Builds understanding of how smaller actions create a complete routine.

3. Include Part-to-Whole Activities

Have students assemble shapes, pictures, or body parts into a whole.

Why it helps: Encourages global visual understanding and top-down organization.

4. Simplify Visual Environments

Avoid excessive posters, patterns, or bright contrasts.

Why it helps: Reduces visual overload, allowing attention to focus on key details.

5. Teach Context Explicitly

Use graphic organizers, summaries, and main idea worksheets.

Why it helps: Helps students connect new information to what they already know.

For School-Based Teams

- Teachers can simplify displays and preview transitions visually.

- Occupational therapists can address sensory regulation through movement and proprioceptive input.

- Physical therapists can add body-based tasks that reinforce attention and coordination.

- Speech-language pathologists can pair visuals with language to help students connect symbols and meaning.

- Special educators can reinforce generalization and big-picture understanding through repetition and structure.

In summary, the research on visual processing and autism shows that autistic individuals often rely on bottom-up sensory processing, focusing on rich sensory details before integrating them into larger patterns. This is not a deficit but a difference. When we understand this processing style, we can design environments and learning tasks that respect the way each student experiences the world transforming potential challenges into strengths.

Reference

Huang, Y., Nobel Norrman, H., Oliva, M., Van Leeuwen, T. M., Fransson, P., Bölte, S., & Neufeld, J. (2025). Local and Global Visual Processing in Autism: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Neuroimaging Studies. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 1-20.