5 Ways to Make IEP Writing Faster Without Losing Individualization

IEP writing is one of those tasks that somehow manages to be both critically important and utterly exhausting. You know the student well. You have clear ideas about what they need. But translating all of that into compliant, measurable, individualized goals and present levels? That can take hours. Hours you don’t have.

The pressure is real: write goals that are specific enough to be meaningful, general enough to allow flexibility, measurable enough to show progress, and individualized enough to reflect this particular student’s needs. Oh, and do it for 15-30 students while also providing services, attending meetings, and managing your daily caseload.

Here’s the truth: faster IEP writing doesn’t mean generic IEPs. It means having systems that help you organize your thinking and translate what you know into compliant documentation efficiently. Here are five ways to speed up the process without sacrificing quality.

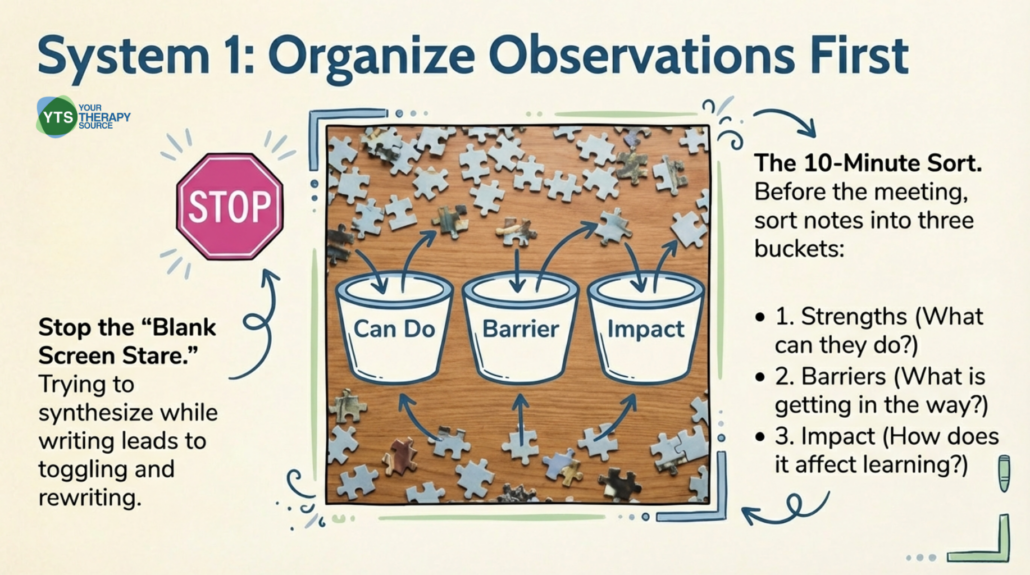

Organize Your Observations Before You Start Writing

The hardest part of IEP writing isn’t the actual typing. It’s the mental work of organizing scattered observations, data points, and clinical impressions into a coherent narrative. When you sit down to write without this organization, you end up staring at a blank screen, toggling between different documents, and rewriting the same section three times.

Instead, create a pre-writing process:

- Keep a running list of strengths, challenges, and functional impacts throughout the year

- Before the IEP meeting, spend 10 minutes sorting your notes into categories: What can the student do? What’s getting in the way? What’s the impact on learning or participation?

- Use a simple framework to capture: current performance → barrier → needed support

When you do this organizing work first, the actual writing becomes much faster. You’re not trying to remember and synthesize and write all at the same time. You’re translating organized thoughts into the IEP format, which is a much simpler task.

Some providers find it helpful to use a structured planning tool that prompts them through this organization process, turning their clinical observations into draft present levels and goal foundations. It’s to have a system that helps you capture and organize what you already know so the writing flows more easily.

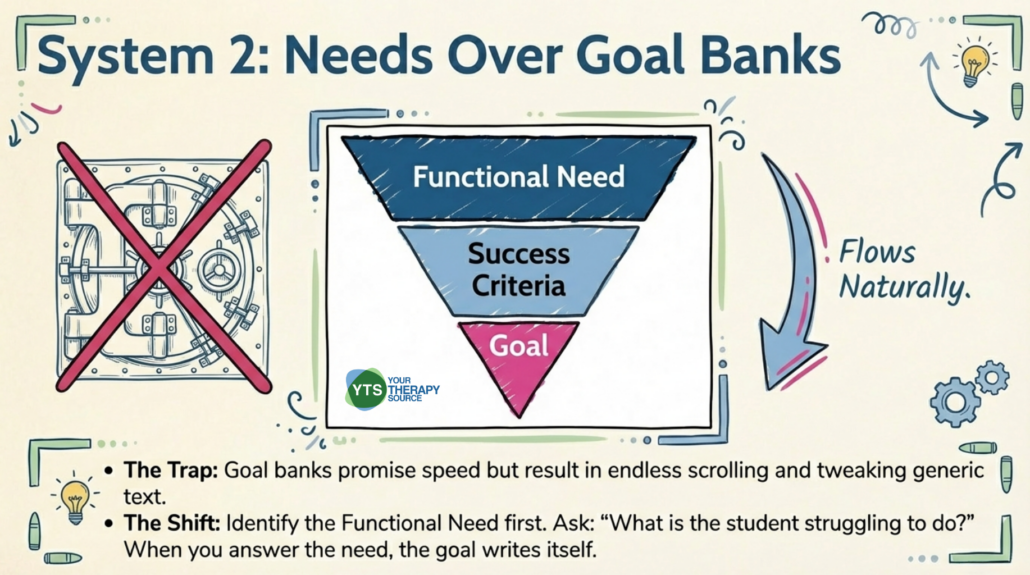

Start With the Student’s Functional Need, Not the Goal Bank

Goal banks are tempting. They promise speed: just find a goal that’s close and tweak it. But here’s what actually happens: you spend 20 minutes scrolling through generic goals, pick one that’s sort of relevant, and then spend another 15 minutes modifying it to actually fit your student. And even then, it often doesn’t quite capture what the student really needs.

Flip the process. Start with the functional need:

- What is this student struggling to do that impacts their learning or participation?

- What would success look like in observable, measurable terms?

- What’s a realistic but meaningful target for growth over the IEP period?

When you start with the actual need, the goal writes itself. You’re not trying to force a pre-written goal to fit. You’re describing what the student needs in a way that happens to meet SMART goal criteria.

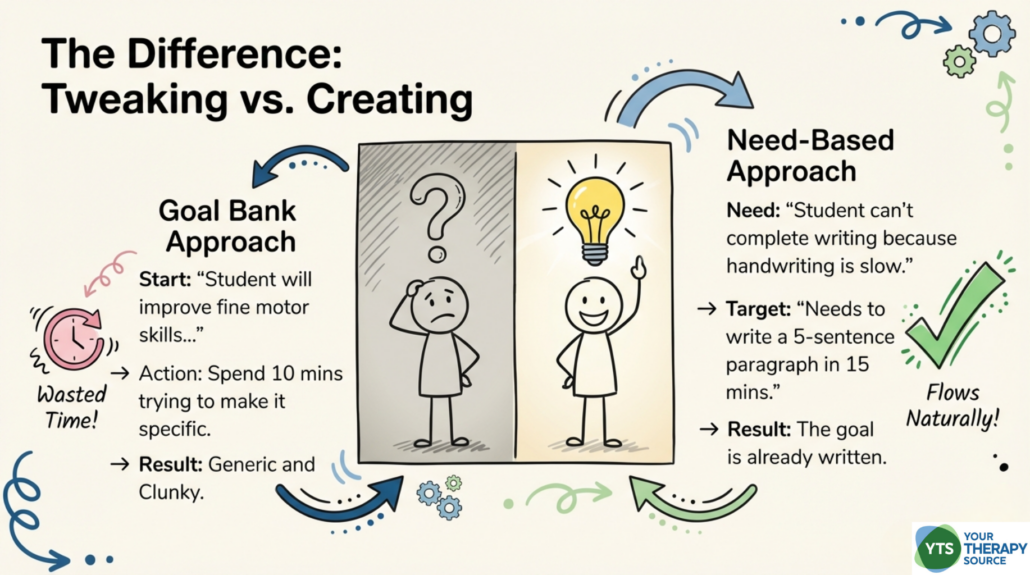

Here’s the difference:

- Goal bank approach: “Student will improve fine motor skills as measured by…” (now spend 10 minutes figuring out how to make this specific to your student)

- Need-based approach: “This student can’t complete written assignments independently because handwriting is slow and effortful. By the end of the IEP period, they need to be able to write a 5-sentence paragraph in 15 minutes.” (the goal practically writes itself)

When you have a framework that helps you move from functional observation to measurable goal efficiently, you spend less time wordsmithing and more time thinking about what the student actually needs.

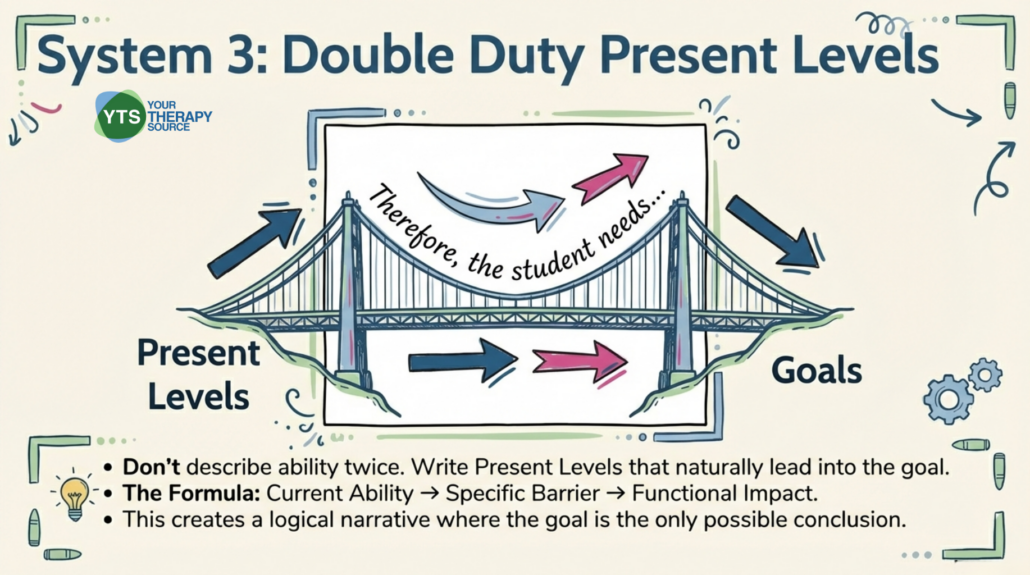

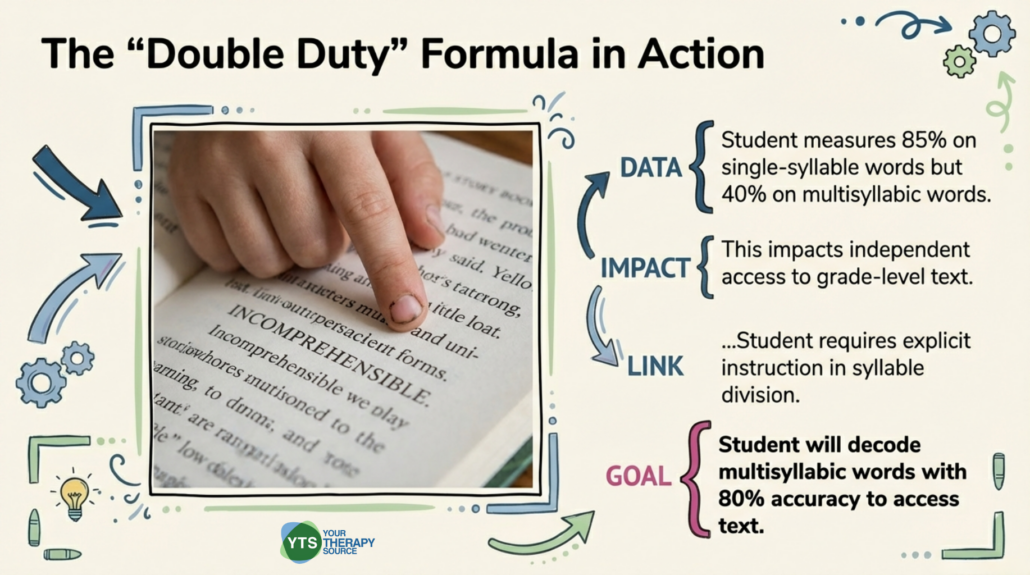

Write Present Levels That Do Double Duty

Present levels are often treated as a separate section from goals, which means you end up describing the student’s abilities twice: once in the present levels and again when justifying the goal. This is inefficient and makes your IEP longer than it needs to be.

Instead, write present levels that set up your goals directly:

- Describe what the student can currently do

- Identify the specific barrier or gap

- Note the functional impact

- (This naturally leads into: “Therefore, the student needs to…”)

Example: “The student can decode single-syllable words with 85% accuracy but struggles with multisyllabic words (40% accuracy). This impacts their ability to access grade-level texts independently, requiring constant adult support during reading activities. The student would benefit from explicit instruction in syllable division strategies.”

Now the goal flows naturally: “The student will decode multisyllabic words with 80% accuracy in order to access grade-level texts more independently.”

When your present levels are written with this structure, goals practically write themselves. And your IEP tells a coherent story rather than feeling like disconnected sections.

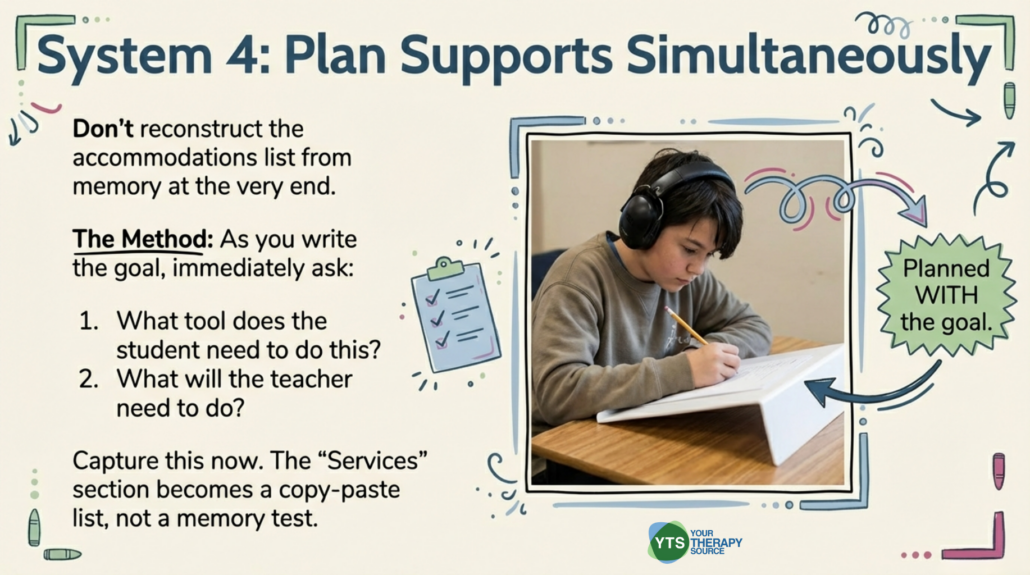

Build Your Accommodations and Services List as You Write Goals

Too often, accommodations and services get added at the end, almost as an afterthought. But this creates extra work: you write the goal, then you have to think back through what supports the student needs, then you have to make sure those supports align with the goal.

Instead, think about supports as you develop each goal:

- What accommodations does the student need to work on this goal?

- What specially designed instruction will you provide?

- How often and in what setting?

- What will teachers need to do in the classroom?

Capture this information as you develop the goal, not afterward. Some providers keep a simple checklist: For each goal, what classroom supports are needed? What direct services? What consultation?

When you’re clear on the support plan while you’re writing the goal, the services and accommodations sections become simple lists rather than sections you have to reconstruct from memory. You’ve already done the thinking. You’re just documenting it.

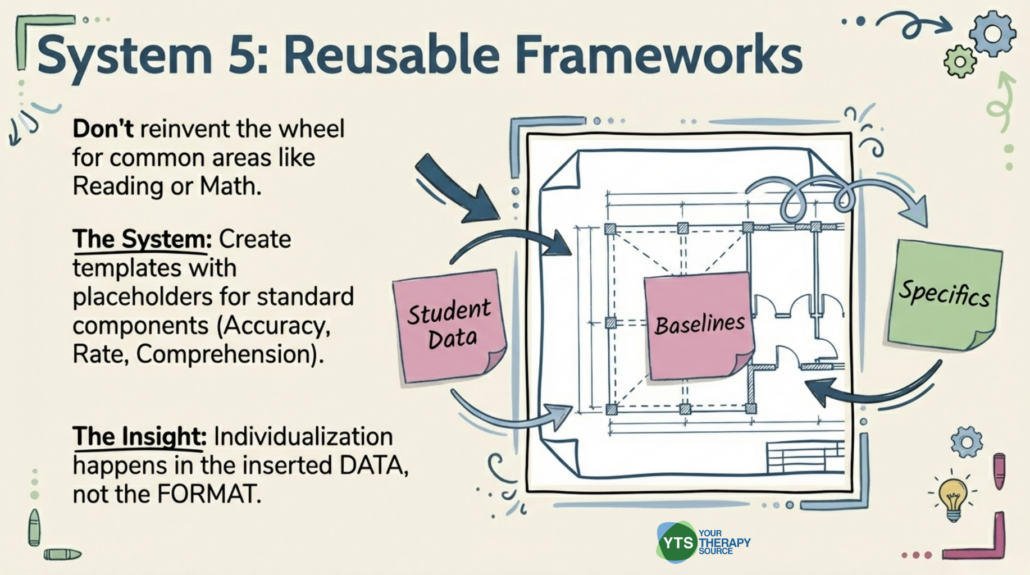

Create a Reusable System for Common Goal Areas

You probably write goals in the same general areas repeatedly: reading fluency, math computation, written expression, social skills, fine motor, executive functioning. While each student is unique, the structure of goals in these areas is often similar.

Create frameworks for your most common goal areas that include:

- Key components to address (for reading: accuracy, rate, comprehension)

- Typical measurement approaches (words per minute, percentage correct, rubric scores)

- Common baseline and target ranges

- Standard accommodations and services for that goal type

This isn’t about using the same goal for every student. It’s about having a starting structure that you customize based on the individual student’s data and needs. You’re not reinventing the goal format every time; you’re personalizing a solid foundation.

When you have these frameworks ready to use, you can generate a draft goal in minutes, then spend your time refining it to reflect this particular student rather than starting from scratch.

The providers who write IEPs fastest aren’t cutting corners. They have systems that help them move from assessment data to organized present levels to clear goals to aligned services efficiently. The individualization happens in the clinical thinking and the specific data points, not in the formatting and organizational work.

The Bottom Line

Faster IEP writing isn’t about lowering standards or using generic language. It’s about having clear processes that help you organize your clinical observations and translate them into compliant documentation efficiently.

When you have frameworks that guide you from “here’s what I’m seeing” to “here’s the present level, goal, and support plan,” you spend less time wrestling with blank pages and more time ensuring each IEP truly reflects what the student needs. The quality comes from your clinical judgment and knowledge of the student. The system just helps you capture it clearly and quickly.

The goal is simple: spend less time on IEP paperwork so you have more time for the work that actually helps students make progress.