Understanding Stimming: Why Kids Do It and How We Can Support Them

Stimming is a natural and meaningful way many children regulate their bodies, emotions, attention, and social experiences. Although stimming is often discussed in relation to autism, it is not unique to autistic children. All humans engage in repetitive actions such as tapping a foot, doodling, pacing, or humming. For many neurodivergent children, stimming is more visible or frequent because it plays a central role in how their brains and bodies interact with the world.

Research grounded in autistic perspectives makes it clear that stimming is not merely a behavior to manage or reduce. It can support regulation, thinking, communication, emotional expression, and social connection. Stimming is most often described as positive by autistic individuals and becomes problematic primarily when it is stigmatized, suppressed, or unsafe (Morris et al., 2025). Understanding this distinction is essential for educators, therapists, and caregivers.

What Is Stimming

Stimming refers to repetitive movements, sounds, or actions that provide sensory input and support regulation. Stimming may be intentional or automatic, subtle or noticeable, calming or energizing. Autistic adults describe stimming as grounding, organizing, joyful, and emotionally expressive, with negative experiences tied almost exclusively to social judgment or self-injury rather than the behavior itself (Morris et al., 2025).

There is no fixed list of behaviors that “count” as stimming. What matters is the function the behavior serves for the individual child.

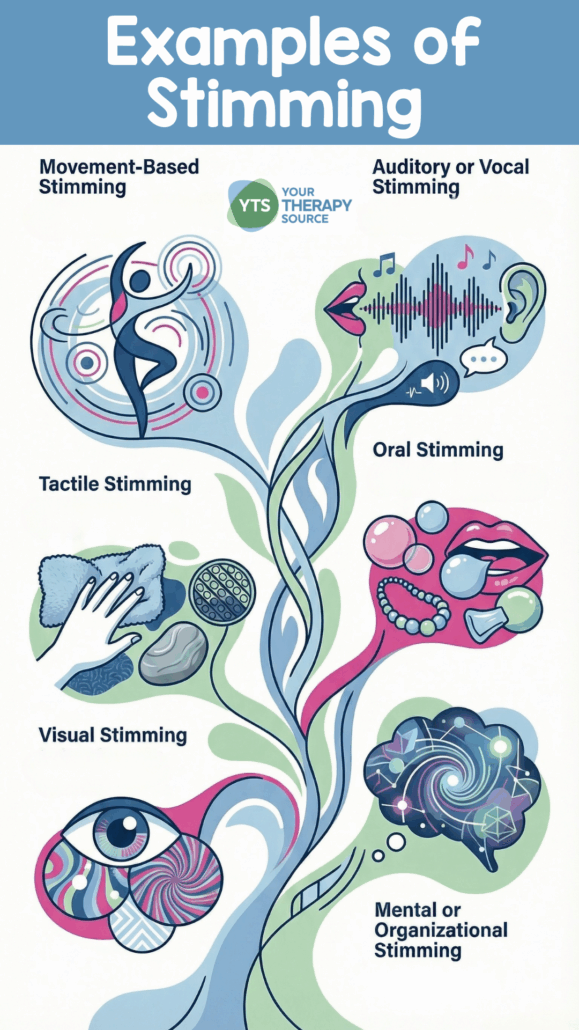

Types of Stimming You Might See

Stimming varies widely across children, contexts, and sensory profiles.

Movement-Based Stimming

Examples include rocking, hand flapping, jumping, spinning, pacing, or shifting posture.

These movements provide vestibular and proprioceptive input that helps regulate arousal, release energy, and support attention.

Tactile Stimming

Examples include rubbing textures, tapping surfaces, squeezing objects, or touching specific materials. These actions offer grounding sensations that help the nervous system feel organized.

Visual Stimming

Examples include watching spinning objects, focusing on light patterns, lining up items, or moving fingers in front of the eyes. Predictable visual input can reduce sensory overload and support emotional regulation.

Auditory or Vocal Stimming

Examples include humming, repeating sounds or words, clicking the tongue, or making rhythmic noises. Auditory input can organize attention, soothe anxiety, or buffer unpredictable environmental noise.

Oral Stimming

Examples include chewing, mouthing objects, or biting materials. Oral input provides deep regulation and can support calming and focus.

Mental or Organizational Stimming

Examples include repeating phrases internally, replaying scenes mentally, or arranging objects in specific patterns. These behaviors support predictability, emotional comfort, and cognitive organization.

What Need Is Being Met When a Child Stims

Stimming is purposeful. Children may stim to manage sensory input, regulate emotional intensity, maintain attention, express joy, cope with uncertainty, or communicate internal states. Research emphasizes that stimming often increases during transitions, cognitive demand, emotional stress, or sensory overload, reflecting an adaptive response rather than a deficit (Tancredi & Abrahamson, 2024).

A helpful guiding question is: What is this behavior helping the child do right now?

How the Brain and Body Process Stimming

Contemporary research reframes stimming as an embodied brain-body process rather than a distraction from learning or communication.

Stimming Regulates the Nervous System

The autonomic nervous system continuously shifts between states of alertness and calm. Stimming provides sensory input that helps the body move toward balance. Some stims calm an overactivated system, while others increase alertness when arousal is too low (Morris et al., 2025).

Stimming Provides Predictable Sensory Feedback

When environments feel chaotic or overwhelming, stimming offers sensations the child can control. This predictability supports emotional safety and reduces stress (Morris et al., 2025).

Stimming Supports Thinking and Learning

Educational research grounded in embodied cognition suggests that stimming can actively support cognition. Movement, fidgeting, and rhythmic activity may reduce cognitive load and help organize thought. From this perspective, stimming is part of the thinking process rather than separate from it (Tancredi & Abrahamson, 2024).

Stimming as Communication and Social Connection

Stimming is not always solitary or private. Research with autistic adults and non-speaking autistic children shows that stimming can carry communicative meaning and support social connection. Shared or interactive stimming can function as a form of communication, particularly when speech is limited or not preferred (Chen, 2024).

Why Suppressing Stimming Can Be Harmful

Many autistic individuals report intentionally suppressing stimming to avoid judgment, a process often referred to as masking. Autistic adults describe masking as physically and emotionally exhausting and closely linked to stress, anxiety, and reduced well-being (Morris et al., 2025).

Importantly, stimming itself is rarely described as harmful by autistic individuals. Harm arises when environments demand conformity rather than accommodation. This highlights the responsibility of educational and social contexts to adapt, rather than expecting children to suppress self-regulatory behaviors.

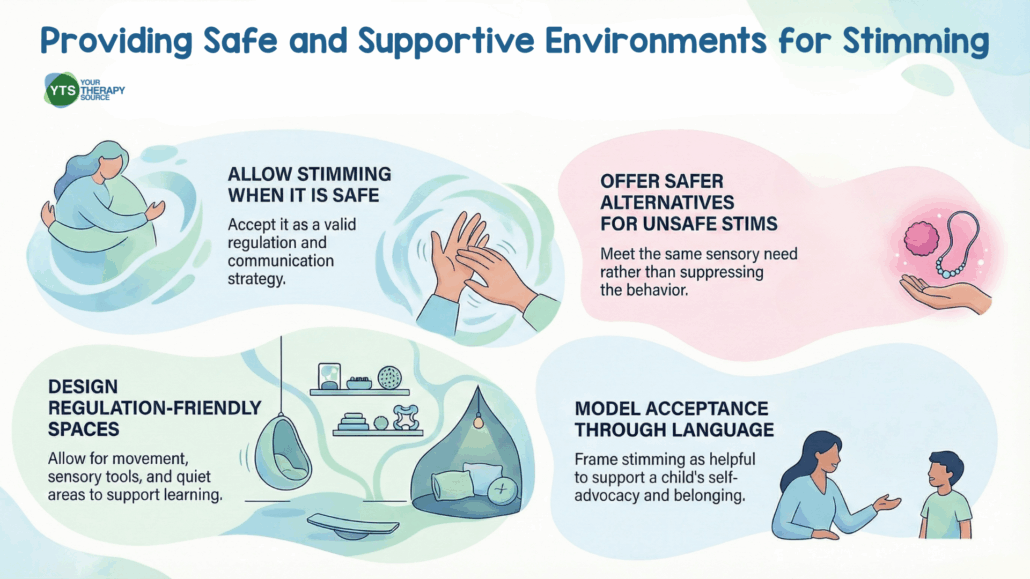

Providing Safe and Supportive Environments for Stimming

The goal is not to eliminate stimming, but to support it safely and respectfully.

Allow Stimming When It Is Safe

When stimming does not cause injury or place the child at risk, it should be accepted as a valid regulation and communication strategy.

Offer Safer Alternatives When Needed

If a stim is self-injurious or unsafe, support should focus on identifying safer alternatives that meet the same sensory need rather than suppressing regulation altogether.

Design Regulation-Friendly Spaces

Classrooms and therapy spaces that allow movement, sensory tools, flexible seating, and quiet areas acknowledge that bodies regulate differently and that movement can support learning (Tancredi & Abrahamson, 2024).

Plan for Shared and Public Settings

When certain stims may place a child at social or physical risk, proactive planning helps preserve dignity. Predictable routines, scheduled breaks, and access to quieter regulation strategies can reduce stress without requiring masking.

Model Acceptance

Adult responses strongly shape how children view their bodies and needs. Language that frames stimming as helpful rather than disruptive supports self-advocacy, safety, and belonging.

When Additional Support May Be Helpful

Collaboration with occupational therapists, physical therapists, speech-language pathologists, or psychologists may be appropriate if stimming is self-injurious, distressing for the child, or signals unmet sensory or emotional needs. Support should prioritize understanding function and supporting regulation, not eliminating stimming. Get access to a FREE printable handout on stimming behaviors.

Stimming as Regulation, Thinking, and Communication

Stimming is not simply a self-regulation behavior. Research grounded in autistic experience demonstrates that it can support emotional balance, cognitive processing, communication, and social connection. When adults shift from control to understanding, children are better able to participate, learn, and feel safe being themselves.

References

Chen, R. S. Y. (2024). Bridging the gap: Fostering interactive stimming between non-speaking autistic children and their parents. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, 18, Article 1374882. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnint.2024.1374882

Morris, I. F., Sykes, J. R., Paulus, E. R., Dameh, A., Razzaque, A., Vander Esch, L., Gruenig, J., & Zelazo, P. D. (2025). Beyond self-regulation: Autistic experiences and perceptions of stimming. Neurodiversity, 3, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/27546330241311096

Tancredi, S., & Abrahamson, D. (2024). Stimming as thinking: A critical reevaluation of self-stimulatory behavior as an epistemic resource for inclusive education. Educational Psychology Review, 36, Article 75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-024-09904-y