Calming Movements – Quick Brain Breaks (No Deep Breaths Needed!)

Classrooms place constant demands on students’ attention, self-control, and emotional regulation. Students are expected to sit, listen, process information, manage sensory input, and shift between tasks throughout the day. When regulation breaks down, common strategies often focus on verbal reminders, breathing exercises, or asking students to “calm down.” These calming movements offer an easy way to provide instant calm in the classroom.

While approaches like deep breathing can be helpful, research suggests that regulation often begins in the body before it can be supported through language or cognition. Brief, intentional movement sequences can help organize the nervous system, supporting attention and readiness to learn without requiring students to stop instruction or engage in complex self-reflection.

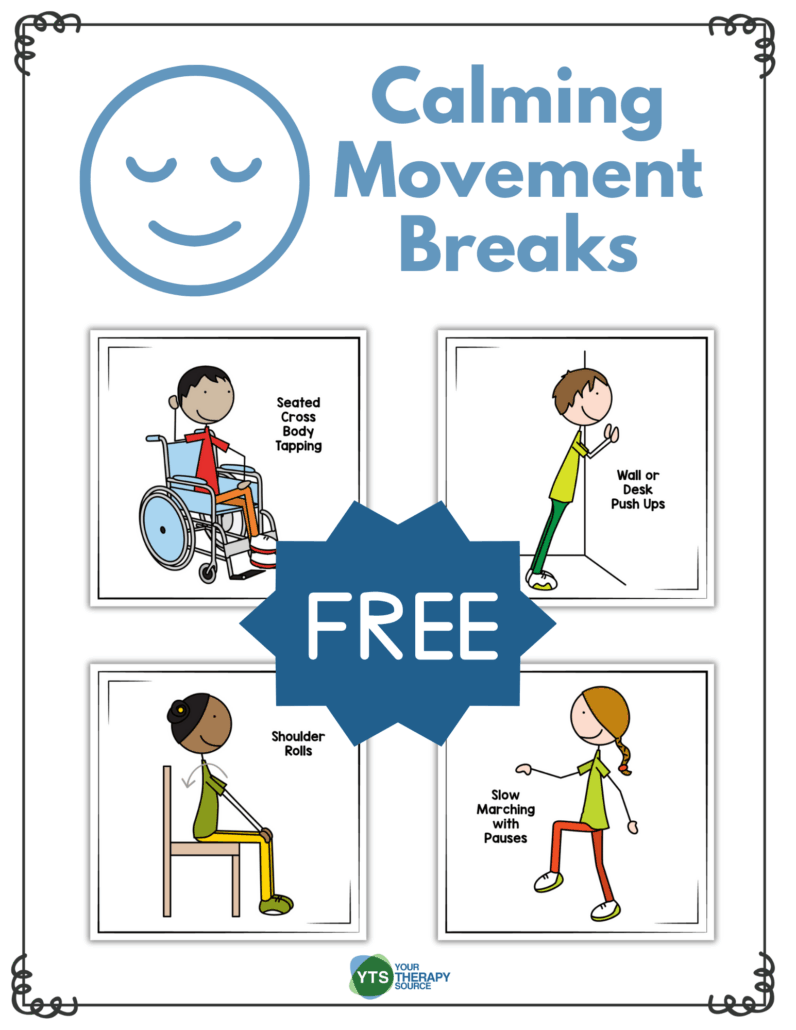

You can download a FREE printable at the bottom of the post.

What the Research Actually Shows About Movement Breaks

Research on classroom-based physical activity is consistent in several key areas. Studies and systematic reviews show that short movement breaks during the school day are associated with improvements in attention, inhibitory control, and on-task behavior in children and adolescents (Donnelly et al., 2016; Janssen et al., 2014; Mahar et al., 2006).

These effects are typically:

- immediate or short-term

- observed after brief bouts of movement (often 1–5 minutes)

- strongest for attention and behavior rather than test scores

Systematic reviews also show that direct improvements in academic achievement are mixed and not guaranteed, especially in short-term studies (Daly-Smith et al., 2018; Watson et al., 2017). However, attention, engagement, and behavioral regulation are well-established prerequisites for learning, and movement supports these foundational skills.

Why Movement Can Support Calm and Focus

Students’ nervous systems continuously respond to sensory, cognitive, and emotional demands. When demands exceed capacity, students may appear restless, disengaged, emotionally reactive, or shut down.

While the exact biological mechanisms are still being studied, research suggests that physical activity can help regulate arousal levels and support executive functioning by:

- interrupting prolonged sedentary behavior

- increasing blood flow and neural activation

- engaging coordination, timing, and motor planning systems

The idea that movement supports regulation through sensory and body-based pathways is consistent with broader neuroscience and occupational therapy frameworks.

The Instant Calm Movement Toolkit for the Classroom – No Equipment Required

The following movement sequences align with research on brief, low-intensity classroom activity. They are designed to be calming, predictable, and easy to implement without disrupting instruction. They are suggestions to help you get started. There are many other exercises you could try as well!

Cross-Body Tapping

Students alternate tapping one hand to the opposite knee, thigh, or desk surface at a slow, steady pace. This can be done seated or standing and works best with a consistent rhythm or count.

Cross-body movements require bilateral coordination and controlled timing. Research on movement breaks suggests that activities involving coordination and cognitive engagement may have stronger effects on attention and executive functioning than passive movement alone (Mavilidi et al., 2015).

This movement is useful during transitions or when students appear scattered or impulsive.

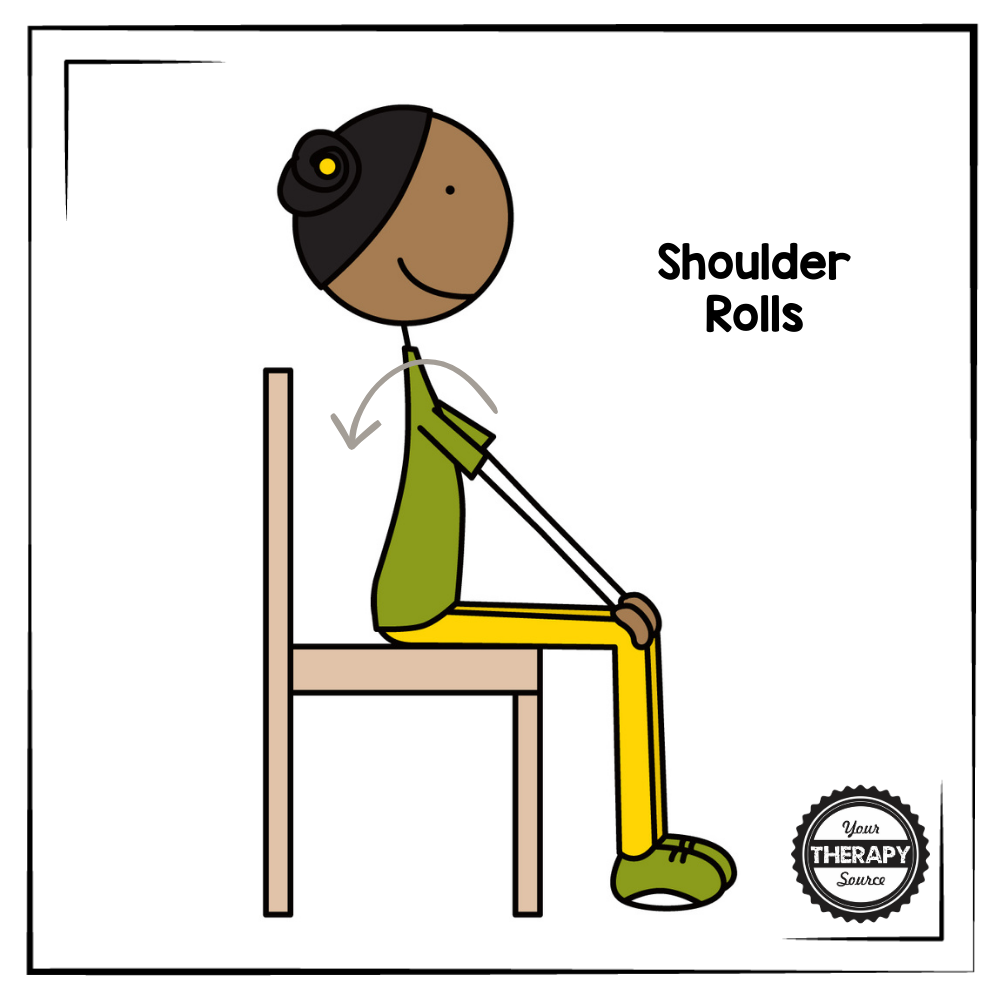

Grounded Shoulder Rolls

Students keep their feet planted while slowly rolling the shoulders backward. Movements should be controlled and unhurried.

This activity supports postural awareness and reduces upper-body tension, which may indirectly support attention during seated academic tasks. While shoulder rolls themselves have not been studied in isolation, low-intensity movement that interrupts prolonged sitting is associated with improved classroom engagement (Watson et al., 2017).

This movement works well during writing, screen use, or visually demanding tasks.

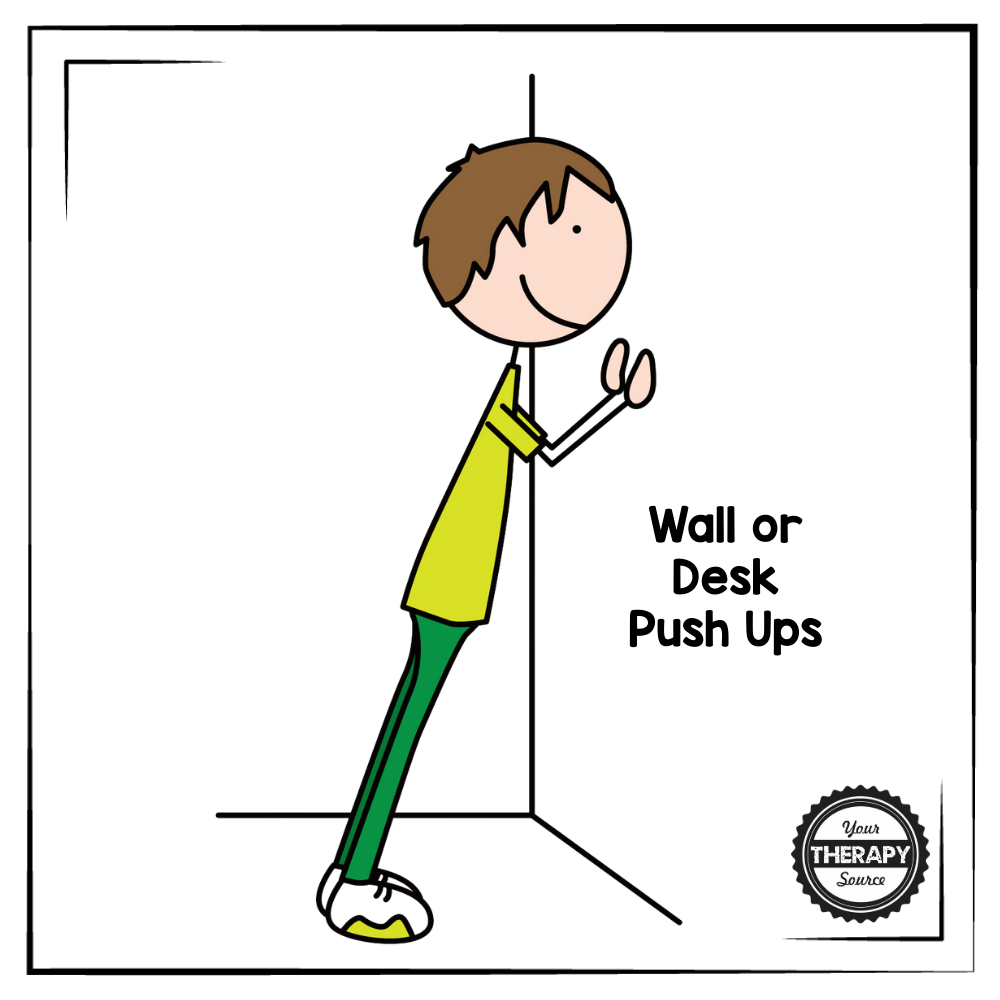

Wall Pushes or Desk Presses

Students place their hands on a wall, desk, or tabletop and gently press forward for several seconds before releasing.

Isometric activities provide strong proprioceptive input and engage large muscle groups without increasing heart rate. Research supports the use of brief physical activity breaks to reduce restlessness and improve on-task behavior, even when movements are simple and quiet (Donnelly et al., 2016).

This option is particularly helpful when students need regulation without added stimulation.

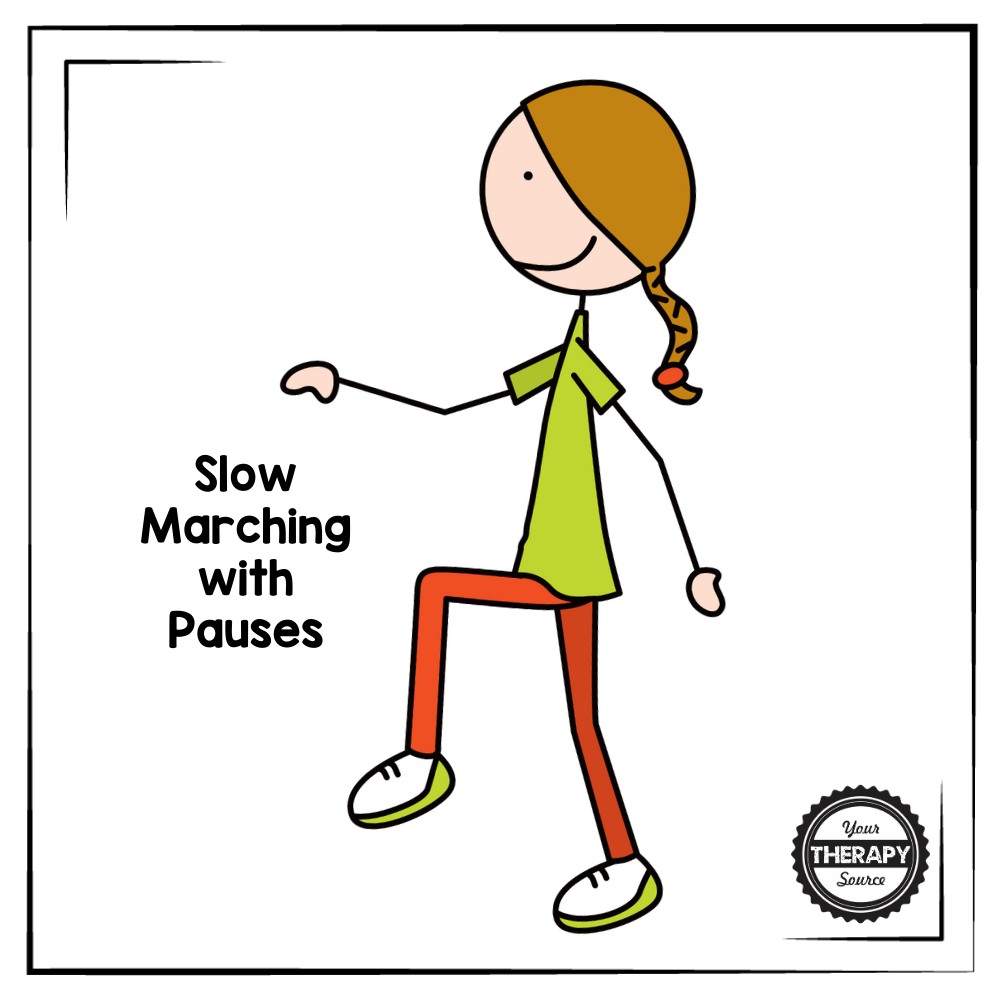

Slow Marching With Pauses

Students march in place slowly, lifting one knee at a time and pausing briefly before switching sides.

Movements that involve balance, timing, and inhibition align with research showing improvements in selective attention following short activity breaks (Janssen et al., 2014). The pause encourages control rather than speed, supporting a shift toward focused engagement.

This movement is useful after higher-energy moments or before returning to seated work.

Practical Guidance for Classroom Use

Movement breaks can be offered to the whole class or quietly suggested as an option for individual students without drawing attention. Research suggests movement breaks are most effective when they are:

- brief and predictable

- integrated into routines

- used proactively rather than only during dysregulation

- framed as support, not correction

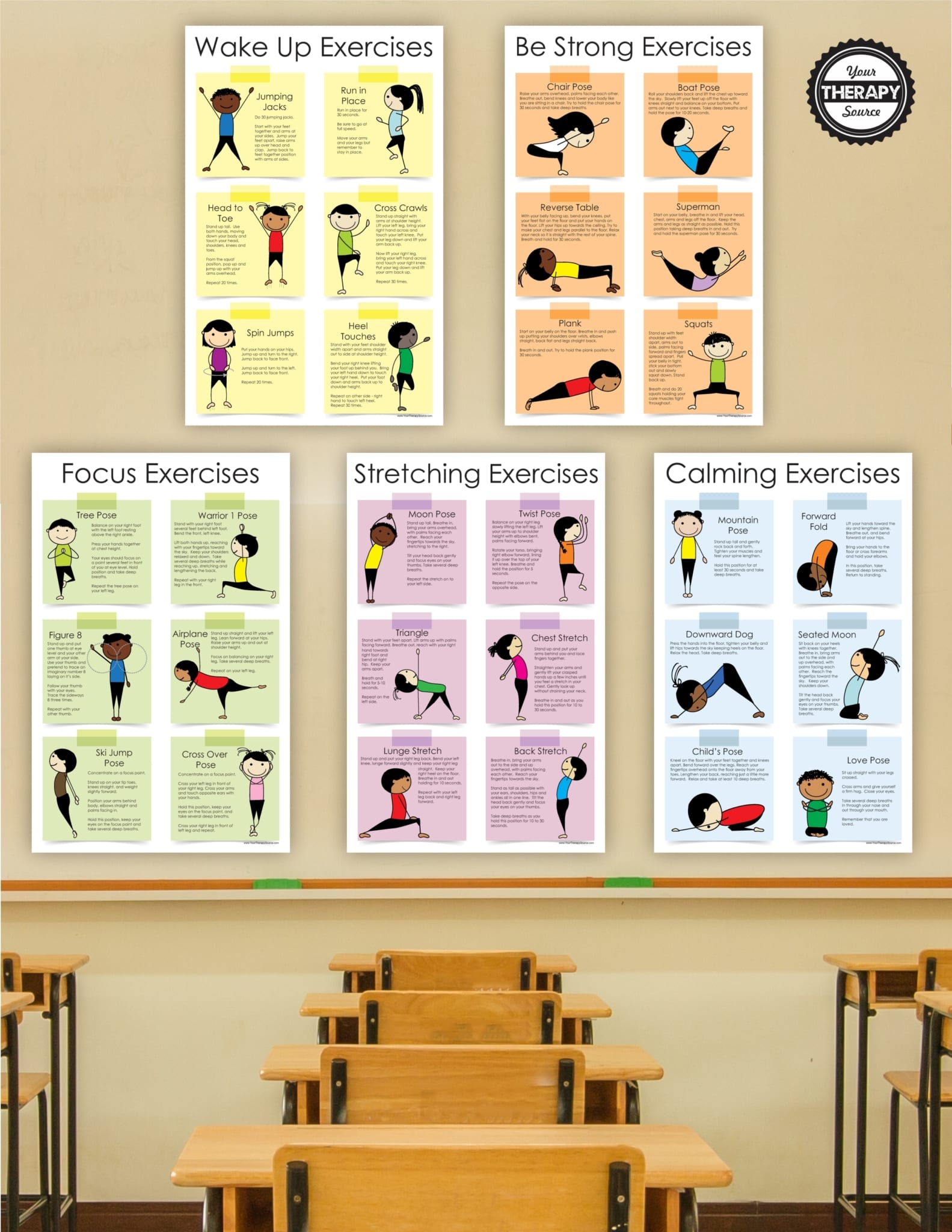

Looking for Other Types of Brain Breaks that Require No Equipment?

Different students benefit from different types of movement depending on their energy and regulation needs. Offering multiple movement options helps educators match strategies to students’ current needs.

For higher-energy movement and active brain breaks, this playlist created by a physical therapist offers a wide range of options.

Why This Matters for Learning

The research is clear that movement breaks can support attention, engagement, and classroom behavior. While they are not a guaranteed way to raise test scores, they help create the conditions students need to participate, focus, and learn. When movement is used intentionally and consistently, it becomes a practical, inclusive tool for supporting regulation in real classrooms.

Download your FREE Calming Movements Printable

Enter your email to access the free printable of the calming movements for quick brain breaks.

References

Daly-Smith, A. J., Zwolinsky, S., McKenna, J., Tomporowski, P. D., & Defeyter, M. A. (2018). Systematic review of acute physically active learning and classroom movement breaks on children’s physical activity, cognition, academic performance and classroom behaviour. Sports Medicine, 48(1), 77–99.

Donnelly, J. E., Hillman, C. H., Castelli, D., Etnier, J. L., Lee, S., Tomporowski, P., Lambourne, K., & Szabo-Reed, A. N. (2016). Physical activity, fitness, cognitive function, and academic achievement in children: A systematic review. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 48(6), 1197–1222.

Janssen, M., Chinapaw, M. J. M., Rauh, S. P., Toussaint, H. M., van Mechelen, W., & Verhagen, E. A. L. M. (2014). A short physical activity break from cognitive tasks increases selective attention in primary school children. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 17(3), 318–323.

Mahar, M. T., Murphy, S. K., Rowe, D. A., Golden, J., Shields, A. T., & Raedeke, T. D. (2006). Effects of a classroom-based program on physical activity and on-task behavior. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 38(12), 2086–2094.

Mavilidi, M. F., Lubans, D. R., Eather, N., Morgan, P. J., & Riley, N. (2015). Acute effects of movement breaks on cognitive performance in elementary school children. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 18(3), 323–328.

Watson, A., Timperio, A., Brown, H., Best, K., & Hesketh, K. D. (2017). Effect of classroom-based physical activity interventions on academic and physical activity outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 14(1), 114.