Sensory Over-Responsivity and Behavior: What Does the Research Say?

When a child reacts intensely to a sound, a fabric texture, a crowded hallway, or bright lighting, adults often wonder why. What is the relationship between sensory over-responsivity and behavior? Research published in the Journal of Neurodevelopmental Disorders offers important insight into what is happening inside the brain during these moments of sensory overload. For educators, occupational therapists, physical therapists, counselors, and parents, this study helps clarify the brain–body connection behind behavior and provides direction for more supportive, informed responses.

Understanding Sensory Over-Responsivity

Sensory over-responsivity, often called SOR, occurs when a child has strong physical or emotional reactions to everyday sensations. These reactions can include covering ears, avoiding touch, crying, shutting down, or becoming overwhelmed by movement, noise, or visual clutter. While common in children with ADHD or learning differences, SOR also occurs in children with no formal diagnosis. Until recently, the biological pathways behind these reactions have been difficult to pinpoint.

Researchers set out to better understand the neural patterns behind SOR in a group of 83 neurodiverse children between ages 8 and 12. These children were evaluated using direct sensory assessments and underwent brain imaging to determine how different areas of the brain communicate with one another.

Sensory and Self-Regulation Toolkit: OT-Approved Strategies for Kids

Two Brain Systems That Shape Behavior

The study focused on how two major brain systems work together during sensory processing:

- The exogenous system is the outward-facing system of the brain. It processes information from the outside world such as touch, movement, and vision. This system notices what is happening around you.

- The endogenous system is the inward-facing system. It manages emotional regulation, attention, decision making, and cognitive control. This system helps you understand what is happening and decide how to respond.

The researchers wanted to see whether children with sensory over-responsivity showed a different balance between these two systems compared to children without sensory sensitivities.

A Distinct Pattern in Children With Sensory Over-Responsivity and Behavior

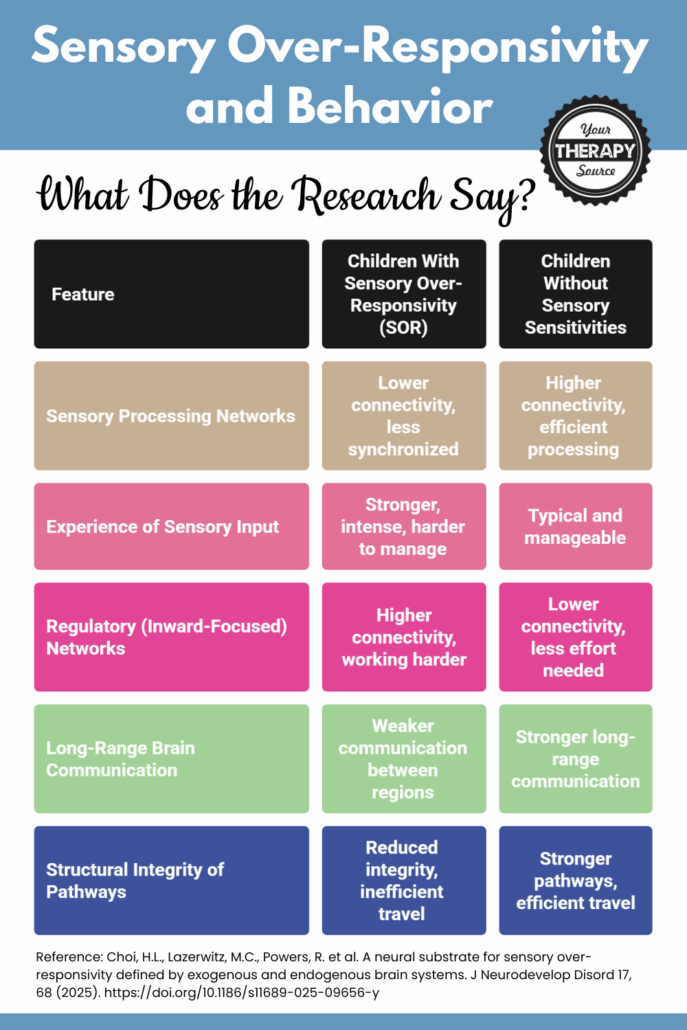

The findings revealed a clear and opposite pattern in how the two groups processed information. Children with sensory over-responsivity had reduced connectivity in the sensory processing networks. Brain regions responsible for vision and motor processing were less synchronized. This suggests that their brains may be dampening sensory input, which can make everyday sensations feel more intense or harder to manage.

At the same time, these children showed increased connectivity in the inward-focused networks responsible for emotional regulation, attention, and cognitive control. These networks appeared to be working harder, possibly as an internal strategy to cope with an overload of sensory information.

Children without sensory challenges showed the opposite pattern. Their sensory networks were well connected, while their internal regulatory networks showed less activation. This created a clear contrast in how the brain organized information depending on whether sensory over-responsivity was present.

The study also found that children with sensory over-responsivity had weaker long-range communication between brain regions and reduced structural integrity in pathways that carry visual, touch, and motor signals. This supports the idea that sensory input may not be traveling efficiently, contributing to overwhelm.

Fun Emotional Intelligence Activities for Kids

An Adaptive Coping Mechanism

The researchers compared these brain patterns with behavior data. Children were grouped as resilient or dysregulated based on parent reports. Resilient children, who were better at adapting to change and recovering from setbacks, showed the strongest pattern of low sensory connectivity and heightened regulatory connectivity.

This suggests that turning inward may be an adaptive coping mechanism. When sensory input becomes overwhelming, the brain may reduce the flow of sensory information and increase inward-focused activity to maintain stability. Children who were more emotionally dysregulated did not show this clear shift between systems, indicating difficulty coordinating these brain networks.

What These Findings Mean for Practice

Although the study did not test interventions, the findings provide meaningful guidance for educators and clinicians who want to understand and support neurodiverse children more effectively. Many challenging behaviors begin with sensory overload rather than intentional actions. When the sensory system is overwhelmed, emotional and cognitive systems work harder to compensate. Understanding this helps shift responses from discipline or correction to support and regulation.

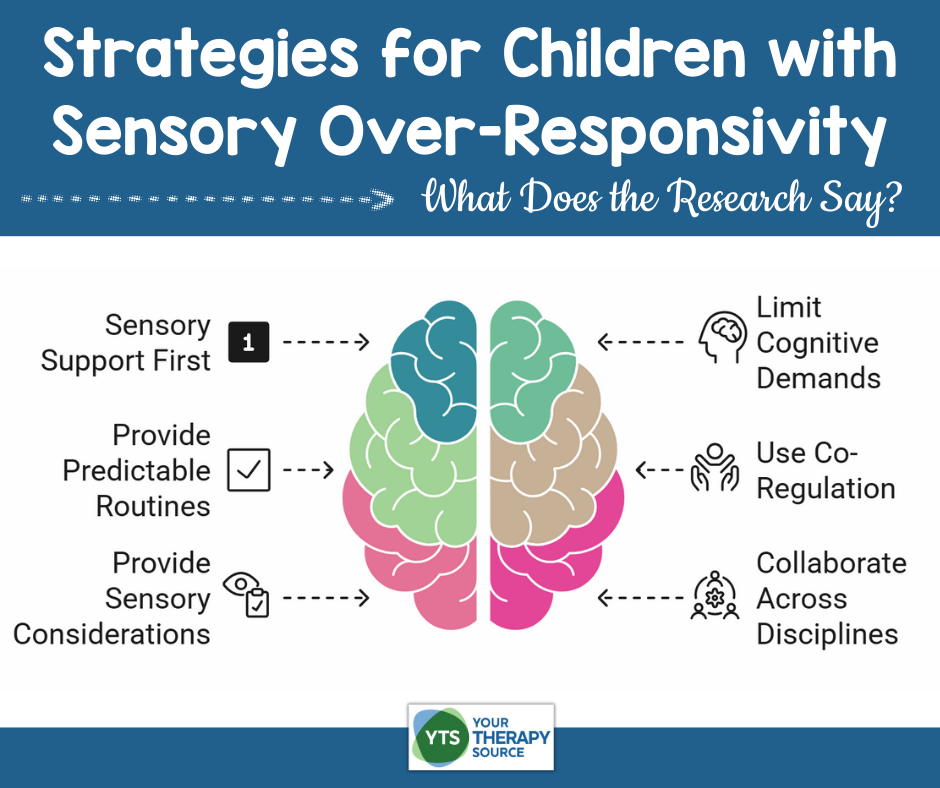

Strategies Supported by the Findings on Sensory Over-Responsivity and Behavior

• Start with sensory support. Reduce sensory load when possible. Provide sensory breaks that include movement, proprioception, or calming activities. This supports the sensory system, which the study found to be less connected in children with SOR.

• Avoid heavy discussions or problem solving during moments of sensory overwhelm. The inward-facing network is already working hard, so added cognitive demands may increase distress.

• Offer predictable routines and clear expectations to reduce unexpected sensory input in the school or home environment.

• Use co-regulation strategies. Instead of expecting a child to independently calm down, model calm breathing, grounding strategies, or quiet presence.

• Incorporate sensory considerations into behavior planning. Before interpreting a behavior as defiance or refusal, consider what sensory factors may have contributed.

• Support interdisciplinary collaboration. Occupational therapists can guide sensory modulation, physical therapists can integrate movement-based regulation, counselors can support emotional awareness and coping, and educators can create sensory-aware routines and classroom environments.

A Broader Understanding of Behavior

This research reinforces that sensory over-responsivity is not simply a behavioral issue. It reflects measurable differences in how the brain processes and responds to information. By understanding the brain–body connection, professionals can respond with strategies that reduce sensory stress, strengthen resilience, and support emotional regulation.

Reference

Choi, H.L., Lazerwitz, M.C., Powers, R. et al. A neural substrate for sensory over-responsivity defined by exogenous and endogenous brain systems. J Neurodevelop Disord 17, 68 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s11689-025-09656-y