Oral Stimming in Students: What Does the Research Say?

Chewing on shirt collars, biting pencils, humming during lessons, or constantly mouthing objects are behaviors that often raise concern in classrooms and at home. These oral stimming actions are sometimes labeled as habits to break or behaviors to stop. However, research across neuroscience, psychology, and developmental science suggests a different interpretation.

For many students, oral stimming is a self-regulatory behavior that helps the nervous system manage alertness, attention, and emotional load. Understanding the science behind these behaviors allows educators and parents to respond in ways that support learning and well-being rather than unintentionally increasing stress.

What Is Oral Stimming?

Oral stimming refers to repetitive movements or sounds involving the mouth, jaw, or vocal system. Examples include:

- Chewing on clothing, pencils, or objects

- Sucking or mouthing nonfood items

- Biting lips or nails

- Humming or making repetitive vocal sounds

- Seeking crunchy or chewy foods

In research literature, these behaviors fall under repetitive motor or sensory behaviors, which are described across development and are especially common in neurodivergent populations (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Who Commonly Uses Oral Stimming?

Oral stimming is something many people engage in at times, such as chewing gum or humming when concentrating, but differences in frequency, intensity, and reliance mean some students use these behaviors more often as a key strategy for self-regulation.

Autism Spectrum Disorder

Repetitive behaviors, including oral sensory behaviors, are a core diagnostic feature of autism. Research consistently shows that autistic individuals experience sensory processing differences at higher rates than neurotypical peers, including differences in oral sensory processing (Lane et al., 2010; Schaaf & Lane, 2015).

Qualitative and quantitative studies indicate that many autistic individuals use stimming—including oral and vocal stims—as a way to regulate sensory input, manage emotional intensity, and cope with environmental demands (Charlton et al., 2021).

ADHD

Individuals with ADHD often engage in self-stimulating behaviors such as fidgeting, movement, or oral activity. Research supports the idea that many people with ADHD experience under-arousal in attention networks and may engage in movement or stimulation to support alertness (Zentall & Zentall, 1983).

While direct experimental evidence specifically linking oral stimming to improved academic performance in ADHD is limited, broader research demonstrates that self-generated movement can be associated with improved consistency and sustained attention in adults with ADHD (Son et al., 2024). This suggests oral behaviors may function as part of a broader self-regulation strategy, even though outcomes vary by task and individual.

Sensory Processing Differences

Some students seek oral input due to sensory processing differences that increase the need for strong tactile or proprioceptive feedback. Chewing activates powerful jaw muscles and sensory receptors that provide proprioceptive input, which is known to influence nervous system regulation (Schaaf & Lane, 2015; Pfeiffer et al., 2011).

What Happens in the Brain During Oral Stimming?

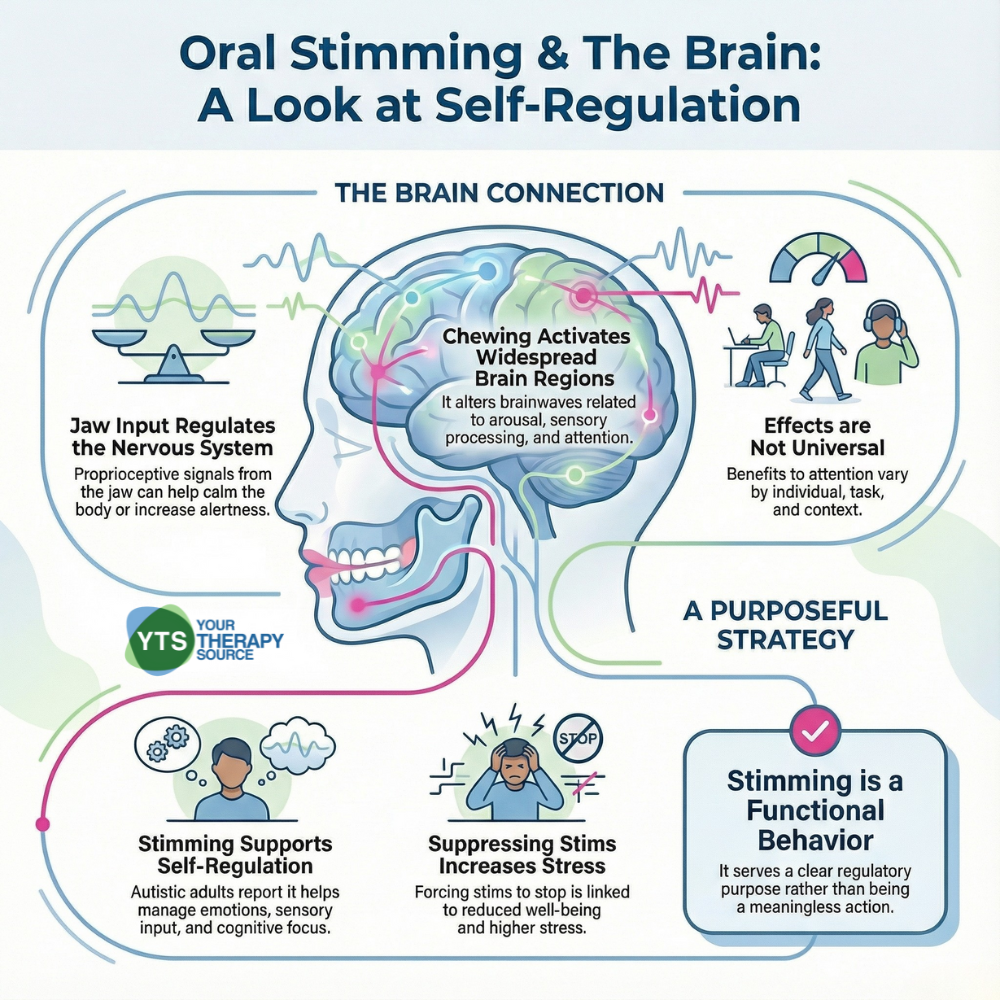

Oral Input and Nervous System Regulation

Proprioceptive input, including input from the jaw, can influence arousal and regulation. Research suggests that proprioceptive input may help modulate nervous system activity, sometimes contributing to calming effects and sometimes increasing alertness, depending on the individual and context (Schaaf & Lane, 2015).

Chewing and Brain Activity

Studies in neurotypical adults show that chewing activates widespread brain regions and alters brainwave activity related to arousal and sensory processing (Hirano & Onozuka, 2015). Chewing has been associated with changes in attention and stress responses, though results vary depending on task demands and population.

Importantly, research does not support universal claims that chewing improves attention for all individuals or all tasks. For example, some studies involving children with ADHD have found neutral or mixed effects on vigilance during structured tasks (Tucha et al., 2010). This highlights the need for individualized interpretation rather than one-size-fits-all conclusions.

Stimming as a Self-Regulation Strategy

Autistic adults report that stimming supports emotional regulation, sensory coping, and cognitive focus. Research indicates that suppressing stimming due to social pressure is associated with increased stress and reduced well-being (Charlton et al., 2021). These findings suggest that stimming often serves a regulatory function rather than being a behavior without purpose.

Why Oral Stimming Often Increases at School

Research and observational studies suggest oral stimming may increase during:

- High cognitive demand

- Sensory overload (noise, visual clutter, social pressure)

- Stress or uncertainty

- Prolonged sitting or low stimulation

From a neurological perspective, these behaviors can reflect the nervous system attempting to maintain an optimal level of arousal for learning and participation.

When Oral Stimming Does Not Require Intervention

Research and neurodiversity-affirming perspectives agree that oral stimming does not inherently need to be eliminated when it is:

- Physically safe

- Not injuring the student

- Not significantly interfering with learning or participation

Suppressing self-regulatory behaviors without providing alternatives may increase anxiety or dysregulation rather than improve outcomes (Charlton et al., 2021).

When Support or Redirection May Be Appropriate

Supportive intervention may be helpful when:

- The behavior poses a safety risk

- Objects being chewed are unsafe or unsanitary

- The student expresses discomfort or frustration

- The behavior significantly limits participation

Research supports replacement rather than removal, meaning the goal is to meet the same regulatory need in a safer or more functional way (Pfeiffer et al., 2011).

Research-Informed Ways to Support Oral Stimming

Provide Safe Oral Alternatives

Offering appropriate oral input aligns with sensory integration frameworks, which emphasize meeting sensory needs rather than suppressing them (Schaaf & Lane, 2015). While controlled trials on specific oral tools are limited, this approach is theoretically grounded in sensory processing research.

Incorporate Oral Input Into Routines

Proactively providing opportunities for chewing or oral input may reduce constant seeking behaviors by supporting regulation before dysregulation occurs (Pfeiffer et al., 2011).

Allow Movement and Fidgeting

Research indicates that self-generated movement can support sustained attention in individuals with ADHD and other neurodivergent profiles (Son et al., 2024). Oral stimming may decrease when other regulatory movement options are available.

Adjust Environmental Demands

Reducing sensory overload, increasing predictability, and breaking tasks into manageable components can reduce the nervous system’s need for compensatory self-stimulation (Lane et al., 2010).

Use Respectful, Strength-Based Supports

Behavioral approaches are most effective when they focus on self-management, autonomy, and dignity rather than punishment or forced suppression (Pfeiffer et al., 2011).

Reframing Oral Stimming Through a Research Lens

Oral stimming is best understood as information, not misbehavior. It reflects how a student’s nervous system responds to sensory, cognitive, and emotional demands. Research does not support the idea that eliminating stimming improves learning outcomes. Instead, evidence suggests that reframing your approach to one of understanding and supporting regulation is more likely to promote engagement and success.

When adults respond with curiosity and flexibility, students are better able to participate, focus, and feel safe in their learning environments. Access a free printable handout on stimming behaviors to help spread awareness.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). APA Publishing.

Charlton, R. A., et al. (2021). “It feels like holding back something you need to say”: Autistic and non-autistic adults’ accounts of sensory experiences and stimming. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 89, 101864. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2021.101864

Hirano, Y., & Onozuka, M. (2015). Chewing and attention: A positive effect on sustained attention. BioMed Research International, 2015, 367026. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/367026

Lane, S. J., Reynolds, S., & Thacker, L. (2010). Sensory over-responsivity and ADHD: Differentiating using electrodermal responses, cortisol, and anxiety. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, 4, 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnint.2010.00008

Pfeiffer, B., Koenig, K., Kinnealey, M., Sheppard, M., & Henderson, L. (2011). Effectiveness of sensory integration interventions in children with autism spectrum disorders: A pilot study. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 65(1), 76–85. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2011.09205

Schaaf, R. C., & Lane, A. E. (2015). Toward a best-practice protocol for assessment of sensory features in ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(5), 1380–1395. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2299-z

Son, J., et al. (2024). A quantitative analysis of fidgeting in ADHD and its relation to sustained attention. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 15, 1162689. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2024.1162689

Tucha, L., et al. (2010). Detrimental effects of gum chewing on vigilance in children with ADHD. Appetite, 55(3), 679–684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2010.10.001

Zentall, S. S., & Zentall, T. R. (1983). Optimal stimulation: A model of disordered activity and performance in normal and deviant children. Psychological Bulletin, 94(3), 446–471. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.94.3.446