Understanding the Emotional Intelligence Brain: How the Amygdala Shapes Student Behavior

When students seem to “snap,” shut down, or lose control, it is easy to assume they are being defiant or disrespectful. In reality, many of these reactions come from automatic processes inside the emotional intelligence brain, the system that helps us identify emotions, read social cues, and regulate behavior. At the center of this system is the amygdala, a small but powerful structure that detects danger and triggers emotional responses. To support students effectively, we need to understand what happens inside their brains and bodies when they enter fight or flight mode, and how we can help them return to calm.

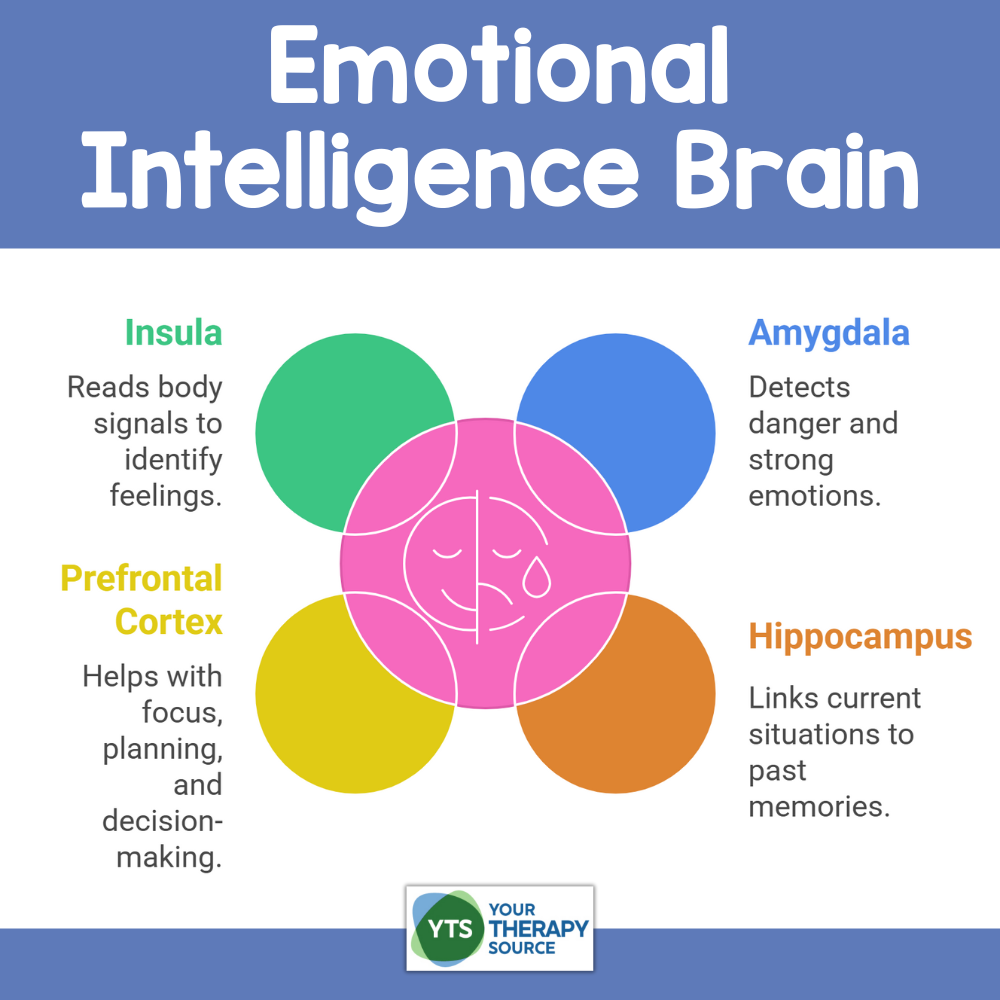

Parts of the Emotional Intelligence Brain

The emotional intelligence brain is made up of several regions that work together to help us notice emotions, manage reactions, and connect with others. These areas include both the limbic system, which is our emotional center, and the prefrontal cortex, which helps with regulation and reasoning.

Amygdala – The Alarm System

The amygdala constantly scans for danger or emotional intensity. It triggers the body’s fight or flight response in less than a second. When it becomes overactive, students may react impulsively or defensively. When balanced, it helps them notice feelings early and respond appropriately.

Hippocampus – The Memory Keeper

The hippocampus sits beside the amygdala. It stores emotional memories and connects past experiences to what is happening now. It helps students remember what worked before and apply coping strategies. When stress is chronic, this area may quiet down, making emotional control harder.

Prefrontal Cortex – The Problem-Solver

Located at the front of the brain, the prefrontal cortex manages reasoning, focus, and impulse control. It helps students pause, think, and make choices. This part of the brain works best when the amygdala is calm.

Insula – The Body’s Emotion Reader

The insula interprets internal sensations (interoception) such as a racing heart or tight muscles and links them to feelings. It helps students notice the physical signs of emotions, such as “My stomach feels tight, I am nervous” or “My shoulders are relaxed, I am calm.” This awareness supports the development of emotional intelligence.

Together, these regions form the emotional intelligence brain. They allow students to recognize emotions, understand what those emotions mean, and respond with empathy and self-control. When any of these areas become overstimulated by stress, behavior often reflects that imbalance.

Self Regulation Workbook – Learn About Yourself

The Amygdala and Self-Regulation

Now that we understand the basics of how the emotional intelligence brain works as a system, it is important to focus on the amygdala. This small structure plays one of the biggest roles in student behavior and self-regulation. The amygdala acts like the brain’s alarm. It constantly monitors the environment for possible threats or strong emotions. When something feels unsafe or overwhelming, it instantly sends signals through the nervous system to prepare the body for action.

During this process, the thinking part of the brain, the prefrontal cortex, temporarily shuts down. This is why a student who is upset cannot reason, follow directions, or reflect on behavior until their body calms. They are not refusing to cooperate. Their nervous system is reacting to protect them.

Once safety cues are restored and the body begins to settle, the prefrontal cortex reconnects with the amygdala. This is when self-regulation becomes possible again. The student can use strategies, think through consequences, and communicate more clearly.

Helping students strengthen the connection between the amygdala and the prefrontal cortex is the foundation of teaching self-regulation. Calming strategies, sensory supports, and trusted relationships all give the brain what it needs to recover and learn.

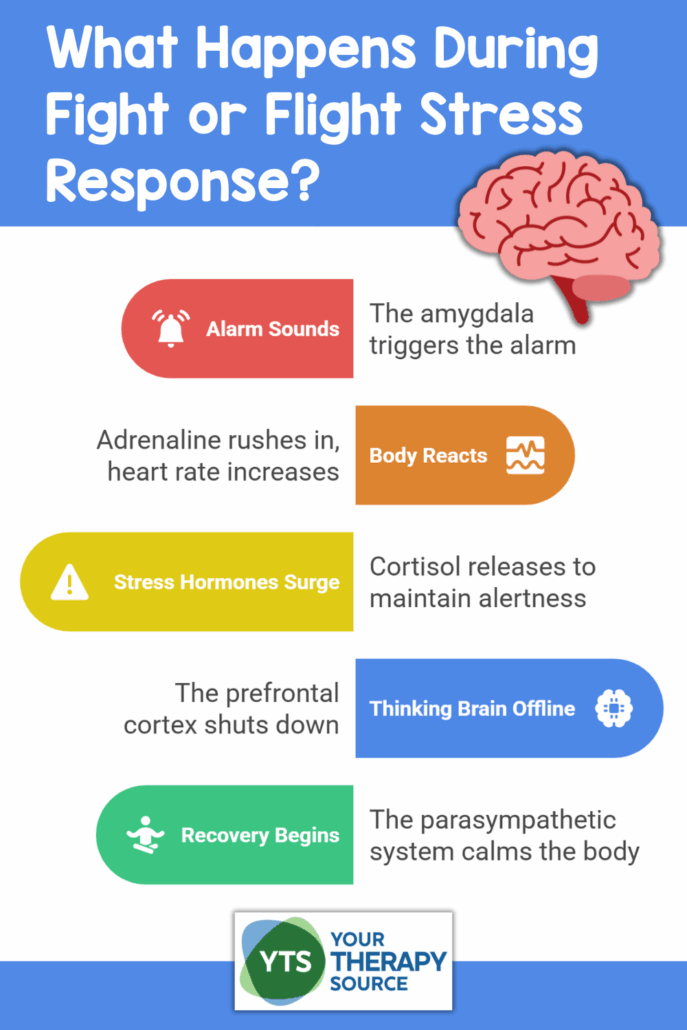

What Happens When the Amygdala Triggers Fight or Flight

Even though these brain areas are designed to work together, the amygdala can take over during moments of stress. When this happens, students move from a state of learning and connection to one of protection and survival.

Here is what happens inside the brain and body, including how long each phase lasts.

Step 1: The Amygdala Sounds the Alarm (0–1 second)

Within a fraction of a second, the amygdala fires and sends an emergency signal throughout the brain and body. The brain reacts automatically, even before a student is aware of the trigger.

Step 2: The Body’s Stress Response (1–3 seconds)

The amygdala alerts the hypothalamus, which activates the autonomic nervous system. The sympathetic branch releases adrenaline, preparing the body to act quickly.

Physical changes occur right away:

- Heart rate and breathing increase

- Pupils dilate

- Muscles tighten

- Digestion slows

This is the body’s survival system at work, preparing for fight, flight, or freeze.

Step 3: The Hormonal Surge (20 seconds–5 minutes)

If the stress continues, the hypothalamus, pituitary gland, and adrenal system release cortisol. This hormone keeps the body energized but makes it harder to learn and remember information. A student may appear angry, restless, or withdrawn. Their emotional intelligence brain is focused on safety, not reasoning.

Step 4: Thinking Brain Goes Offline (0–10 minutes)

As cortisol rises, the prefrontal cortex temporarily shuts down. During this time, a child cannot think clearly or process directions. Reasoning or lecturing will not help until the body calms.

Step 5: Calming and Recovery (10–60 minutes)

Once the student feels safe again, the parasympathetic nervous system activates the body’s rest and digest response. Heart rate and breathing slow, cortisol decreases, and the thinking brain reconnects with emotional centers. Depending on the student and the situation, this process can take anywhere from ten minutes to an hour.

The Amazing Brain Workbook for Kids

Why This Matters for Emotional Intelligence

When students learn how their brain and body work together, they begin to build emotional intelligence. They learn to notice emotions, label them, and choose a healthy response. Teaching about the amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex helps students understand that strong emotions are not “bad.” They are signals from the body that need attention. Building emotional intelligence in the classroom means helping students feel safe enough for their thinking brain to stay in control.

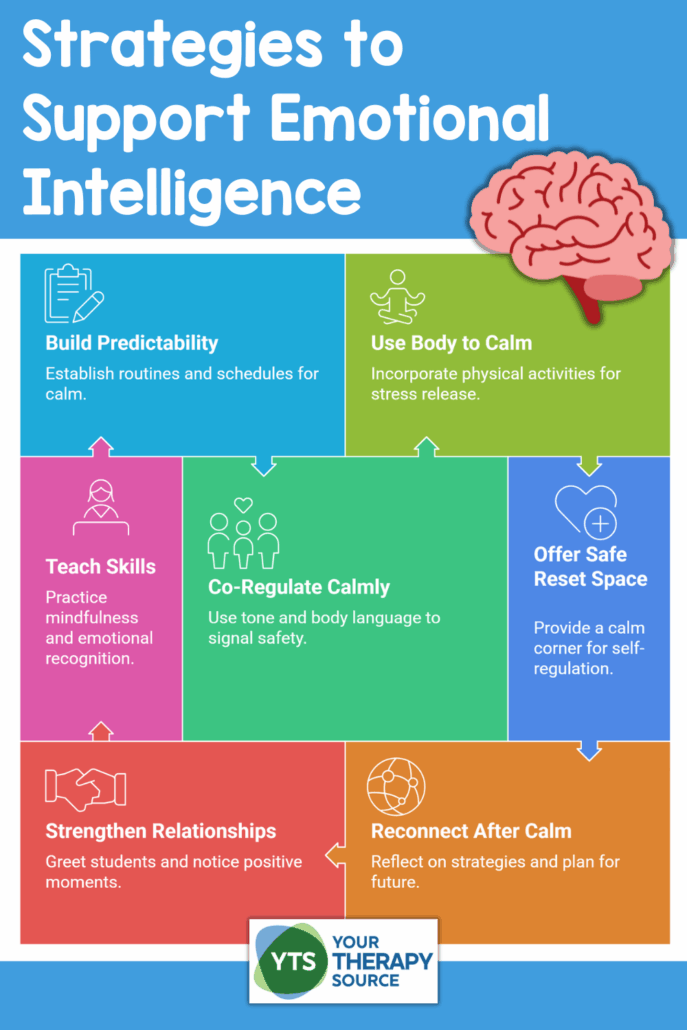

Classroom Strategies to Support Emotional Intelligence

These ideas offer flexible options for supporting students when stress or strong emotion takes over. Choose one or two that fit your teaching style, your students, and your classroom setting.

Understanding the Brain

- Introduce the idea that the amygdala acts as the brain’s alarm and the prefrontal cortex helps with thinking. Try these FREE Calm Brain worksheets and coloring pages.

- Use visuals, stories, or short videos to show how emotions affect the body.

- Encourage curiosity by asking, “What might your brain be trying to tell you?” to prevent student shutdown.

- Share simple reminders that feelings are messages, not misbehavior.

Recognizing Signs of Stress

- Look for small physical changes such as tense posture, fidgeting, or shallow breathing.

- Observe emotional cues such as frustration, withdrawal, or silence.

- Offer early support through calm tone, proximity, or gentle redirection.

- Notice patterns that show when and where students struggle most.

Calming the Classroom Environment

- Keep routines predictable and explain schedule changes in advance.

- Use visual timers or cues for transitions.

- Provide short movement or sensory breaks during the day.

- Adjust lighting or sound levels to create a soothing atmosphere.

- Offer calm, quiet tasks after high-energy activities.

- Teach deep breathing techniques.

Co-Regulation in Action

- Speak slowly and use fewer words when students are upset.

- Maintain a relaxed posture and neutral facial expression.

- Model calming techniques such as breathing or stretching.

- Validate emotions by acknowledging what students feel.

- Take time to regulate yourself before addressing challenging behaviors.

Building Self-Regulation Skills

- Practice calming strategies during morning meetings or transitions.

- Use visuals like feelings scales or emotion thermometers.

- Encourage students to identify which strategies help them feel calm.

- Celebrate small successes when students manage emotions effectively.

- Provide opportunities for reflection when students regain control.

Creating a Safe Reset Space

- Designate a space where students can take a break to calm down.

- Include sensory tools, visuals, or soft textures that promote relaxation.

- Teach routines for using and leaving the area so it feels predictable.

- Emphasize that it is a recovery space, not a consequence.

Strengthening Relationships

- Greet students by name and acknowledge their presence each day.

- Notice effort, kindness, and improvement rather than only outcomes.

- Ask students about their interests and include them in activities.

- Create classroom rituals that build connection, such as end-of-day reflections or gratitude moments.

Collaborating with Teams and Families

- Discuss self-regulation strategies during team meetings or planning sessions.

- Collaborate with therapists, counselors, or other support staff.

- Use consistent language about “brain and body calm” across settings.

- Share what works at school so families can reinforce it at home.

- Continue learning about emotional regulation and brain-based supports.

The Takeaway: Calming the Emotional Intelligence Brain

When a child’s behavior looks reactive, it often means their emotional intelligence brain has been hijacked by the amygdala. Instead of asking, “What is wrong with you?” we can ask, “What happened to you, and what do you need right now?” By modeling calm behavior, creating predictability, and fostering connection, we help students rebuild balance in their brains. When the brain feels safe, learning and growth naturally follow.