How Self-Talk Can Help Students Regulate Emotions and Stay on Track

Affirmations are everywhere in education right now: posters, sticky notes on desks, locker mirrors, and classroom doors. For students, those simple phrases like “I can handle this,” “I’m still learning,” or “I can calm my body” aren’t just feel-good slogans. They are one small piece of a much bigger system: how children use language with themselves to manage attention, effort, and emotions. Learn more about how self talk can help students regulate emotions and stay on track.

Psychologists call this “self-talk,” “private speech,” or “inner speech,” depending on whether it’s spoken aloud or silently in the mind. A growing body of research shows that the way students talk to themselves is closely linked to self-regulation and emotion regulation across childhood, adolescence, and adulthood (Alderson-Day & Fernyhough, 2015; Geva & Fernyhough, 2019).

What the Research Says About Self-Talk and Self-Regulation

Self-talk is not a magic fix but together these studies show how it can support self-regulation. It is a practical, teachable way for students to strengthen how they regulate behavior and emotions when combined with supportive relationships and classroom structures.

- Private speech predicts later emotion regulation in young children. In a longitudinal study, 3-year-olds who used more mature private speech (talking themselves through a puzzle) showed better inhibitory control at age 4, which in turn predicted better emotion regulation at age 9, especially for children who were higher in temperamental anger (Whedon et al., 2021).

- Effort-based self-talk boosts math for low-confidence students. In a field experiment with 4th–6th graders, students practiced either effort self-talk (“I will do my very best!”), ability self-talk (“I am very good at this!”), or no self-talk between halves of a standardized math test. Effort self-talk specifically improved performance for students with negative competence beliefs, breaking the link between low confidence and low scores (Thomaes et al., 2020).

- Inner speech supports executive control. A major review found that inner speech is strongly involved in tasks that demand cognitive control, such as focusing attention, switching between tasks, holding information in mind, and inhibiting impulsive responses, which are all key components of self-regulation (Alderson-Day & Fernyhough, 2015).

- Inner speech grows out of children’s out-loud self-talk. Developmental work shows that children’s private speech (talking themselves through tasks out loud) gradually becomes internal “inner speech” as the brain’s language networks mature. This shift from overt to internal self-talk is viewed as a key pathway for the development of self-regulation (Geva & Fernyhough, 2019; Winsler et al., 2009).

- Distanced self-talk (using your own name) helps people stay calmer. In two high-powered experiments, silently talking to yourself using your own name and “you” (“Ariana, you can handle this”) reduced emotional reactivity when people reflected on negative experiences of varying intensity, including in individuals high in emotional vulnerability (Orvell et al., 2021).

- Third-person self-talk regulates emotion without extra effort. Using third-person self-talk (“You can get through this”) reduced neural markers of emotional reactivity in EEG and fMRI studies without increasing signs of cognitive strain, showing that it may be a relatively “low-effort” emotion regulation strategy (Moser et al., 2017).

- Inner speech is tied to how we regulate emotions. Research on adults has linked patterns of inner speech to both emotion dysregulation and the strategies people use, such as cognitive reappraisal (reframing a situation) or suppression (pushing emotions down). The way people talk to themselves affects how they manage feelings (Salas et al., 2018).

- Mindfulness, self-talk, and self-regulation are interconnected. In a study of university students, inner speech and mindfulness awareness showed a positive relationship. Mindfulness, especially acceptance, was positively associated with self-regulation and self-concept clarity, while mind-wandering was negatively associated with self-regulation. The authors suggest that self-focused attention, self-acceptance, and self-concept clarity may connect self-talk and self-regulation (Racy & Morin, 2024).

Positive Affirmations for Students

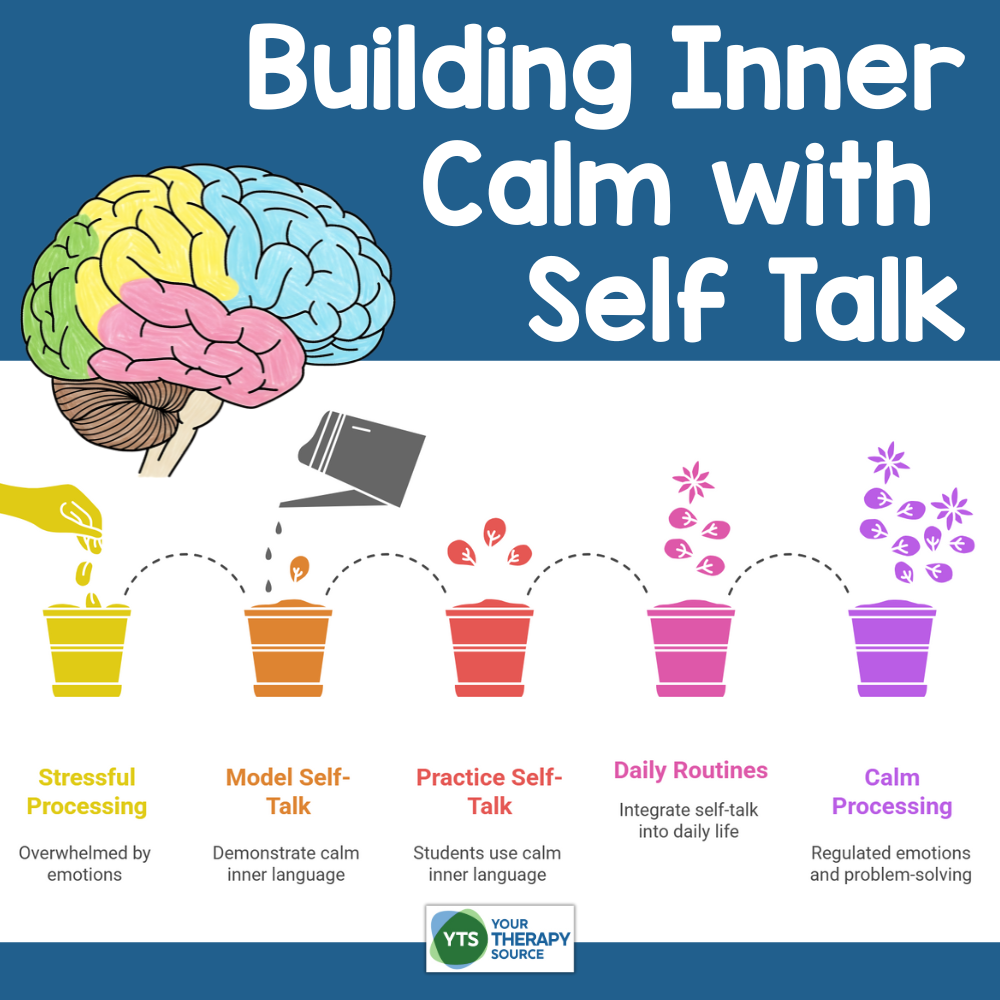

Turning the Research Into Classroom Practice

Here are ways to translate the science into routines, prompts, and language for students without turning your classroom into a wall of empty slogans.

1. Normalize strategic self-talk (including whispering to themselves)

If private speech is an important bridge to inner speech and self-regulation, then a certain amount of “talking yourself through it” is not misbehavior. It is practice (Geva & Fernyhough, 2019; Winsler et al., 2009; Whedon et al., 2021).

Try these strategies:

- Tell students: “Sometimes, quietly talking yourself through a problem helps your brain focus.”

- Use sentence stems: “First I will…,” “Next I need to…,” “If I get stuck, I can…”

- Teach a “whisper voice” or “just-in-my-head voice” for older students who still rely on self-talk.

2. Emphasize effort-focused affirmations for students who doubt themselves

Thomaes and colleagues found that effort-focused self-talk improved math performance for children with negative competence beliefs, while ability-focused self-talk (“I’m good at this”) did not (Thomaes et al., 2020).

Use phrases like:

- “I will do my best on each question.”

- “I can keep trying even when this feels hard.”

- “I can use the strategies I’ve been taught.”

Integrate these into class routines:

- Before a quiz, ask students to say one effort statement quietly three times.

- Provide small desk cards with effort-based phrases for quick reminders.

Try this affirmation song and coloring sheet.

3. Teach “distanced” self-talk for big feelings

Orvell and colleagues found that shifting from “I” to your own name or “you” when thinking about upsetting events can reduce emotional reactivity across a wide range of situations (Orvell et al., 2021). Moser and colleagues add that this shift does not require extra cognitive effort (Moser et al., 2017).

Model it aloud: “If I’m nervous, instead of saying ‘I can’t do this,’ I might think, ‘[Name], you’ve done hard things before. You can breathe and start with step one.’”

Encourage students to write their own supportive phrases: “[Name], you can slow down and read that again.” or “[Name], you can ask for help or try another strategy.”

4. Connect self-talk to emotion regulation strategies

Research suggests that inner speech is related to the emotion regulation strategies people use (Salas et al., 2018; Orvell et al., 2021).

Pair each regulation skill with example self-talk:

- Labeling feelings: “I notice my heart is racing. I’m feeling anxious, not in danger.”

- Reappraisal or Reframing: “This is not a disaster. It’s a challenge I can work through step by step.”

- Coping steps: “First I pause and take three breaths. Then I look at the directions again.”

5. Link self-talk with mindfulness and attention

Racy and Morin found that mindfulness and self-talk are positively linked, while mind-wandering is negatively linked to self-regulation (Racy & Morin, 2024).

Combine a short mindfulness pause with a gentle self-talk cue such as:

- “Thoughts can come and go. I can choose which ones to follow.”

- “I can notice this feeling and still make a good choice.”

6. Adjust affirmations by age group

Private speech peaks in early childhood and gradually becomes internalized into inner speech. Younger children may need more out-loud practice, while older students may benefit more from silent scripts and reflection (Geva & Fernyhough, 2019; Winsler et al., 2009).

Younger students (K–2): Encourage them to whisper steps: “Cut, glue, then color.” Use choral call-and-response: “What do we tell ourselves when it’s tricky?” “I can keep trying!”

Upper elementary and middle school: Include written self-talk prompts in planners or notebooks.

High school and beyond: Have students design their own self-talk scripts for specific situations such as exams or social stress.

Positive Messages Mazes

Research-Informed Affirmations for Students

The most effective affirmations are specific, realistic, and connected to action or coping strategies, not just general positivity. Here are some examples:

Effort and persistence (Thomaes et al., 2020):

- “I will do my best on each step.”

- “I can keep going even if this feels hard.”

Emotion regulation and distancing (Orvell et al., 2021; Moser et al., 2017):

- “[Name], you can breathe and take this one step at a time.”

- “You’ve handled tough moments before. You can handle this one too.”

Attention and planning (Alderson-Day & Fernyhough, 2015; Geva & Fernyhough, 2019):

- “First I’ll read the directions slowly, then I’ll start with question one.”

- “If I get confused, I will pause, reread, and ask for help.”

Self-kindness and acceptance (Racy & Morin, 2024; Salas et al., 2018):

- “It’s okay to feel upset. I can still choose what I do next.”

- “I can talk to myself the way I would talk to a good friend.”

Why This Research Matters

Understanding the science behind self-talk helps educators, therapists, and parents move beyond simple encouragement. When we intentionally teach students how to use language to guide their thoughts, actions, and emotions, we equip them with a lifelong self-regulation skill. By combining affirmations, effort-based language, and strategies grounded in neuroscience, we help children not only believe in themselves but also learn how to stay calm, focused, and resilient when challenges arise.

References

Alderson-Day, B., & Fernyhough, C. (2015). Inner speech: Development, cognitive functions, phenomenology, and neurobiology. Psychological Bulletin, 141(5), 931–965. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000021

Geva, S., & Fernyhough, C. (2019). A penny for your thoughts: Children’s inner speech and its neurodevelopment. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1708. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01708

Moser, J. S., Hartwig, R., Moran, T. P., Jendrusina, A. A., & Kross, E. (2017). Third-person self-talk facilitates emotion regulation without engaging cognitive control: Converging evidence from ERP and fMRI. Scientific Reports, 7, Article 4519. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-04047-3

Orvell, A., Vickers, B. D., Drake, B., Verduyn, P., Ayduk, O., Moser, J., Jonides, J., & Kross, E. (2021). Does distanced self-talk facilitate emotion regulation across a range of emotionally intense experiences? Clinical Psychological Science, 9(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702620951539

Racy, F., & Morin, A. (2024). Relationships between self-talk, inner speech, mind wandering, mindfulness, self-concept clarity, and self-regulation in university students. Behavioral Sciences, 14(1), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010055

Salas, C. E., Castro, O., Radovic, D., Gross, J. J., & Turnbull, O. H. (2018). The role of inner speech in emotion dysregulation and emotion regulation strategy use. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 50(2), 79–88. https://doi.org/10.14349/rlp.2018.v50.n2.1

Thomaes, S., Tjaarda, I., Brummelman, E., & Sedikides, C. (2020). Effort self-talk benefits the mathematics performance of children with negative competence beliefs. Child Development, 91(6), 2211–2220. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13347

Whedon, M., Perry, N. B., Curtis, E. B., & Bell, M. A. (2021). Private speech and the development of self-regulation: The importance of temperamental anger. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 56, 213–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2021.03.013

Winsler, A., Fernyhough, C., & Montero, I. (Eds.). (2009). Private speech, executive functioning, and the development of verbal self-regulation. Cambridge University Press.