Little Kids, Big Feelings, Smart Strategies

Young learners, especially those with developmental delays or disabilities, often experience more challenges with expressing emotions in safe, healthy ways. Difficulties with executive functioning, communication, or inhibitory control can make it harder for them to recognize emotions, choose appropriate strategies, and advocate for their needs. Without explicit instruction, children may rely on behaviors such as yelling, running away, or shutting down when faced with stress. Little kids with big feelings requires smart strategies to help them with their emotional regulation.

Coping skills are protective. They not only help children respond to immediate emotional challenges but also reduce risks for loneliness, depression, and ongoing stress. Teaching coping strategies in the classroom through modeling, practice, and individualized supports. This creates a foundation for both emotional well-being and academic success.

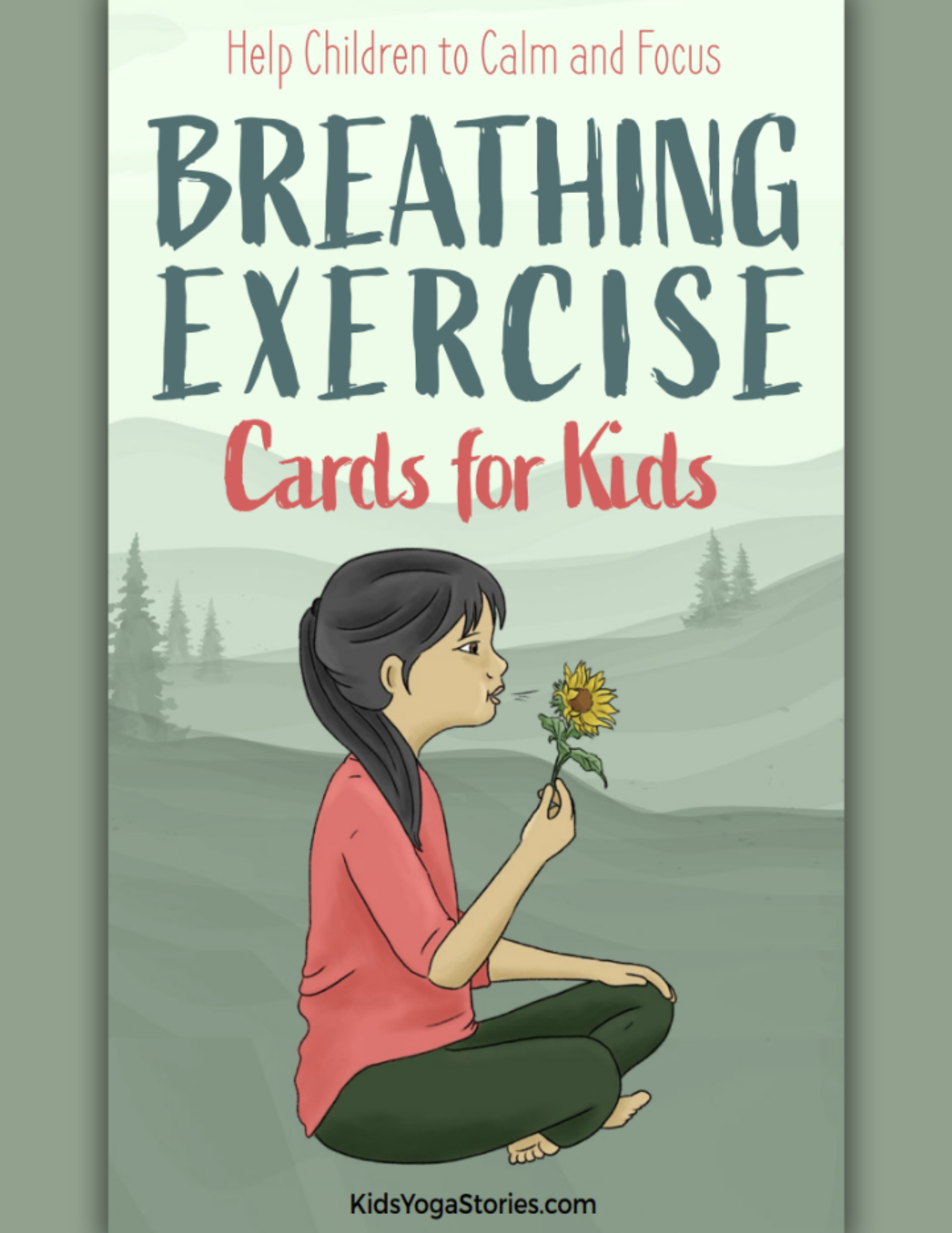

Breathing Exercise Cards For Kids – Digital Version

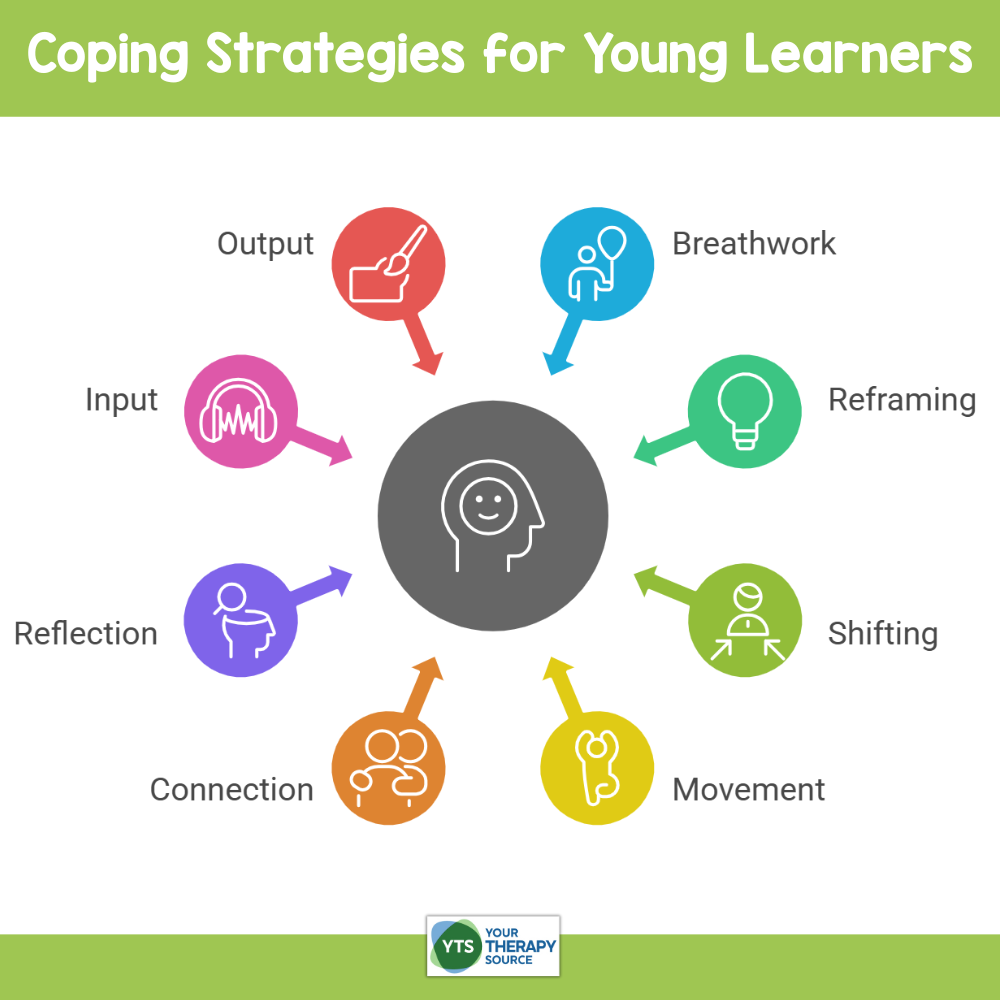

The Eight Core Coping Strategies

Research highlights eight categories of coping strategies that teachers and service providers can embed throughout the day. Each strategy is flexible and can be adapted to children’s communication styles, preferences, and needs.

Breathwork

What it is: Breathing techniques that calm the body and regulate strong emotions.

Examples:

- Balloon breathing (pretend to blow up a balloon).

- Candle breathing (slowly blow out fingers as candles).

- Bubble or dandelion breathing (long exhales).

When to use it: Breathwork is especially useful for children who tend to withdraw or become quiet when upset. It gives them an internal tool they can use independently once practiced. However, for highly energetic children, stillness may feel frustrating, so other strategies may be better in the moment.

Reframing

What it is: Thinking about a stressful situation in a new way, often through positive self-talk.

Examples:

- “Cleaning up is hard, but then I get to play outside.”

- “Waiting is tough, but it means I’ll have my turn soon.”

When to use it: Reframing is helpful during predictable stressors like transitions or non-preferred tasks. It is best introduced when children are calm and can hear adult models of positive self-talk. Over time, children may begin to generate their own reframes.

Shifting

What it is: Redirecting attention toward something more manageable or enjoyable.

Examples:

- Giving a child a preferred role during cleanup.

- Starting with easier problems before harder ones.

- Talking briefly about a favorite topic to calm down.

When to use it: Shifting is powerful during transitions or moments when children are “stuck” on a frustration. It helps prevent escalation while still keeping the child engaged in classroom routines.

Movement

What it is: Safe, physical outlets that allow children to release stress and energy.

Examples:

- Stretching, yoga, or jumping jacks.

- Squeezing a stress ball or using resistance putty.

- Taking a walk in the classroom or hallway.

When to use it: Movement is critical for children who show physical signs of distress (e.g., pacing, kicking, or leaving the room). Proactively teaching safe alternatives ensures they can release energy without unsafe behavior.

Connection

What it is: Seeking support or comfort from others to process emotions.

Examples:

- Talking with a teacher or trusted peer.

- Sitting near a supportive adult.

- Asking for help during a conflict.

When to use it: Connection works well for children who communicate best through interaction or co-regulation. For children who prefer to process emotions alone first, this strategy may be offered later, once they are ready to engage.

Reflection

What it is: Thinking or talking about emotions to build self-awareness and problem-solving.

Examples:

- Labeling feelings: “I feel frustrated right now.”

- Discussing body signals: “My fists are tight, and my voice is loud.”

- Drawing or journaling about emotions.

When to use it: Reflection is most effective when children have already been introduced to emotion words and visuals. It can also be practiced during calm moments, such as after read-alouds or class discussions about characters’ feelings.

Input

What it is: Calming sensory experiences that provide physical comfort.

Examples:

- Listening to soothing music.

- Sitting under a weighted blanket.

- Hugging a trusted adult or using fidgets.

When to use it: Input is especially useful for children who seek comfort from sensory experiences, such as closeness, touch, or calming sounds. Individualization is important—family input helps ensure strategies match the child’s sensory profile.

Output

What it is: Creative or verbal expression of emotions.

Examples:

- Drawing or painting about feelings.

- Singing, dancing, or making music.

- Talking out loud to a trusted adult.

When to use it: Output strategies are powerful for children who enjoy art, music, or expressive play. They are particularly helpful when children cannot yet articulate their feelings with words.

Embedding Coping Strategies Throughout the Day

Coping instruction is most effective when woven into classroom routines. Teachers can model strategies during transitions, integrate them into academic instruction, and use real-time conflicts as teaching moments. For example:

- During a schedule change, a teacher might say, “It’s okay to feel sad. I’ll use my reframing strategy and think about the fun things still coming today.”

- While reading a story, children might reflect: “How is the character feeling? What coping strategy could they use?”

- During a conflict, a teacher can prompt: “I see your fists are tight. Do you want to take deep breaths with me or use the paintbrushes while you wait?”

These authentic opportunities help children practice strategies in meaningful contexts.

Individualizing for Each Child

No single strategy works for all children. Educators can:

- Use visuals of coping strategies and emotions to provide choices.

- Create personalized storybooks showing the child using strategies.

- Build coping kits with items like stress balls, bubbles, or drawing supplies.

- Incorporate family input to align school strategies with what works at home.

- Watch for early signs of distress to prompt strategies before emotions escalate.

Every child will face moments of big emotions in the classroom. When coping skills are explicitly taught, modeled, and practiced, children learn to view emotions not as disruptions but as opportunities for growth. By equipping young learners with a range of strategies: breathwork, reframing, shifting, movement, connection, reflection, input, and output, teachers and related service providers foster independence, resilience, and long-term success.

Reference

Scott, S. M., Taylor, A. L., & Hemmeter, M. L. (2025). Individualized Coping Skills Instruction in the Inclusive Classroom. Young Exceptional Children, 10962506251357290.