Anxiety and Visual Processing

Classrooms place constant demands on visual attention. Students are expected to manage busy walls, worksheets, screens, peer movement, and instructional materials throughout the day. While some students move through these environments with ease, others appear quickly overwhelmed or fatigued. Understanding how trait anxiety and visual processing are associated can help educators and therapists think more clearly about how visual demands may influence attention, regulation, and participation in school settings.

WHAT IS TRAIT ANXIETY?

Trait anxiety refers to a stable tendency to experience heightened vigilance, worry, or sensitivity to environmental demands across situations. Unlike short-term anxiety that arises in response to a specific event, trait anxiety reflects a consistent pattern in how a person notices, processes, and responds to information over time.

Common features associated with trait anxiety include:

- Increased awareness of environmental detail

- Heightened alertness to potential challenges or errors

- Greater effort required to filter out irrelevant input

- Faster overload in complex or busy settings

Trait anxiety is not a diagnosis. It exists along a continuum and can be present to varying degrees in both children and adults.

WHAT THE RESEARCH EXAMINED ABOUT ANXIETY AND VISUAL PROCESSING

The research examined whether individuals with higher levels of trait anxiety process visual information differently at very early stages of brain activity. Across four experiments, young adult participants completed visual tasks while researchers measured brain responses using high-density electroencephalography.

The focus was on early visual processing, which occurs within milliseconds of seeing something and before conscious attention or interpretation. This stage of processing helps the brain register fine visual detail, contrast, and structure. The study explored whether early visual responses were stable over time and whether they differed based on levels of trait anxiety.

Calm and Strong: Songs for Self Calming

Bring calm and confidence to your students!

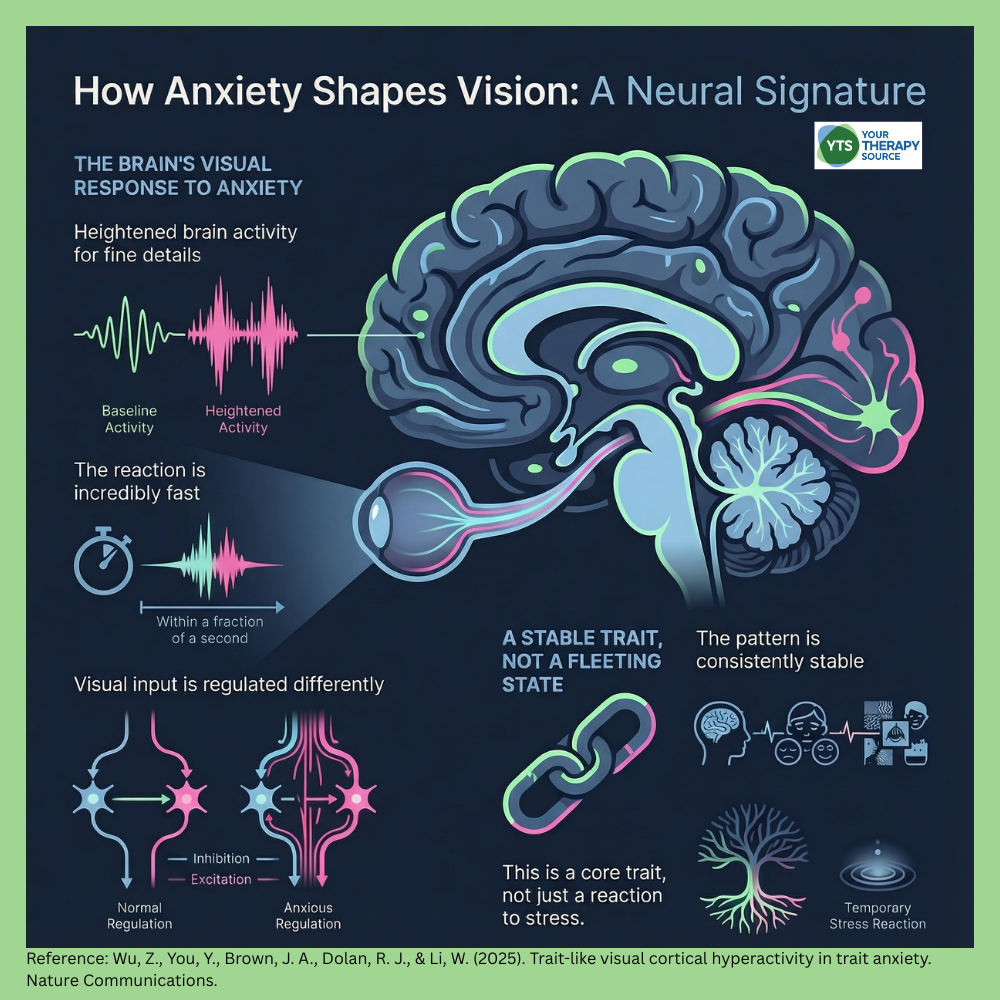

KEY FINDINGS FROM THE RESEARCH

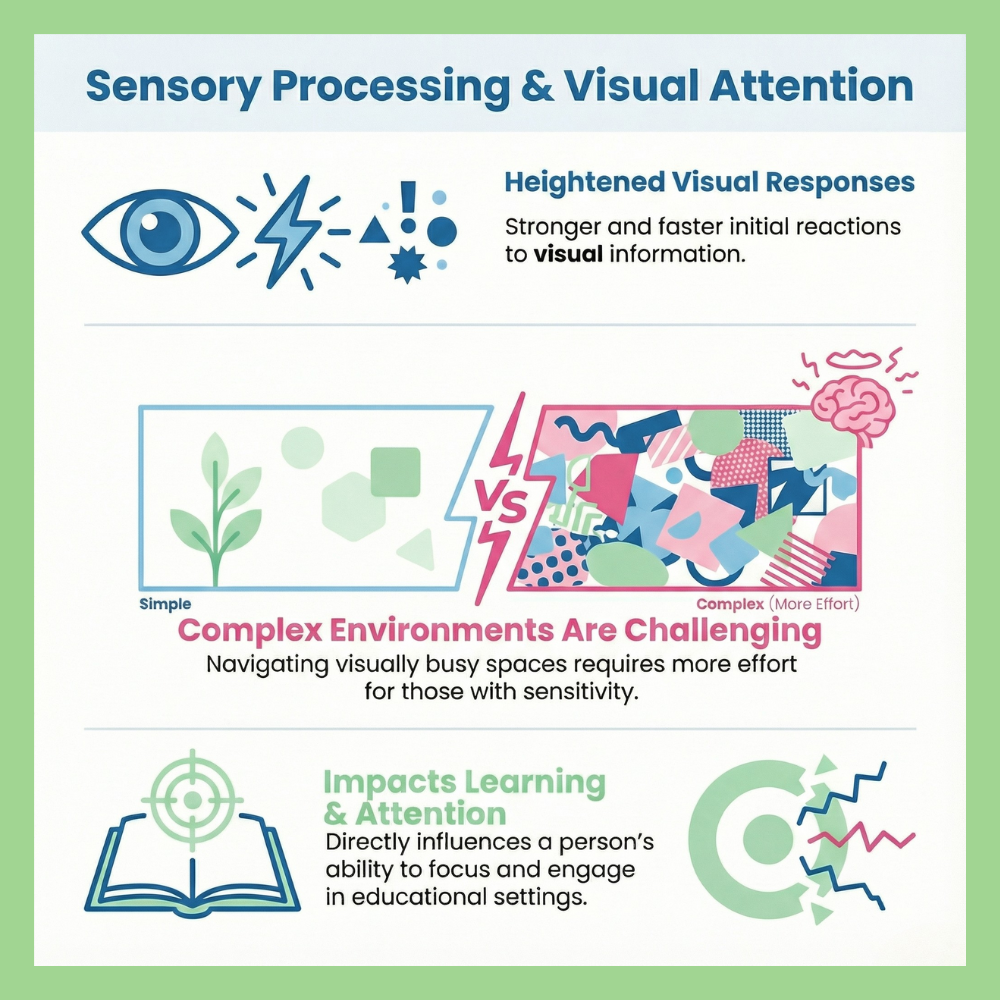

The study identified a consistent association between trait anxiety and visual processing. Key findings included:

- Higher trait anxiety was associated with stronger early brain responses to detailed visual input

- These differences appeared almost immediately after visual information was presented

- The pattern remained stable across time, emotional state, and different types of visual stimuli

- Measures related to neural regulation were less predictive of visual responses in individuals with higher trait anxiety

These findings suggest that anxiety-related differences may begin at the level of how visual information is initially processed, rather than only during later interpretation or emotional response.

WHY THESE FINDINGS MATTER FOR SCHOOL-BASED PRACTICE

Although the research was conducted with young adults, the findings offer a useful framework for thinking about sensory processing demands in schools. Visual complexity is unavoidable in educational settings and often increases as academic expectations rise.

If a student has a tendency toward heightened early visual processing, visually dense environments may require more effort to manage. Information that others filter automatically may feel more demanding, leading to fatigue, reduced attention, or increased stress during learning activities.

This perspective does not suggest that visual input causes anxiety. Instead, it highlights how visual demands and anxiety-related sensory processing patterns may interact in ways that affect participation.

Shapes of Stillness: A Calming Neurographic Art Series

Discover how simple neurographic art can help you and your students’ breathe, focus, and create a sense of calm.

IMPLICATIONS FOR SCHOOL STAFF FOR ANXIETY AND VISUAL PROCESSING

For school-based professionals, this research supports viewing anxiety and sensory processing as interconnected rather than separate concerns.

In practice, this may help explain why some students:

- Struggle to stay focused in visually busy classrooms

- Appear overwhelmed by crowded worksheets or dense visual layouts

- Fatigue quickly during reading, writing, or screen-based tasks

- Show increased worry or avoidance when visual demands are high

Considering visual load alongside emotional and cognitive demands supports more comprehensive problem-solving and environmental planning.

VISUAL CLUTTER CHECKLIST FOR CLASSROOMS AND WORKSHEETS

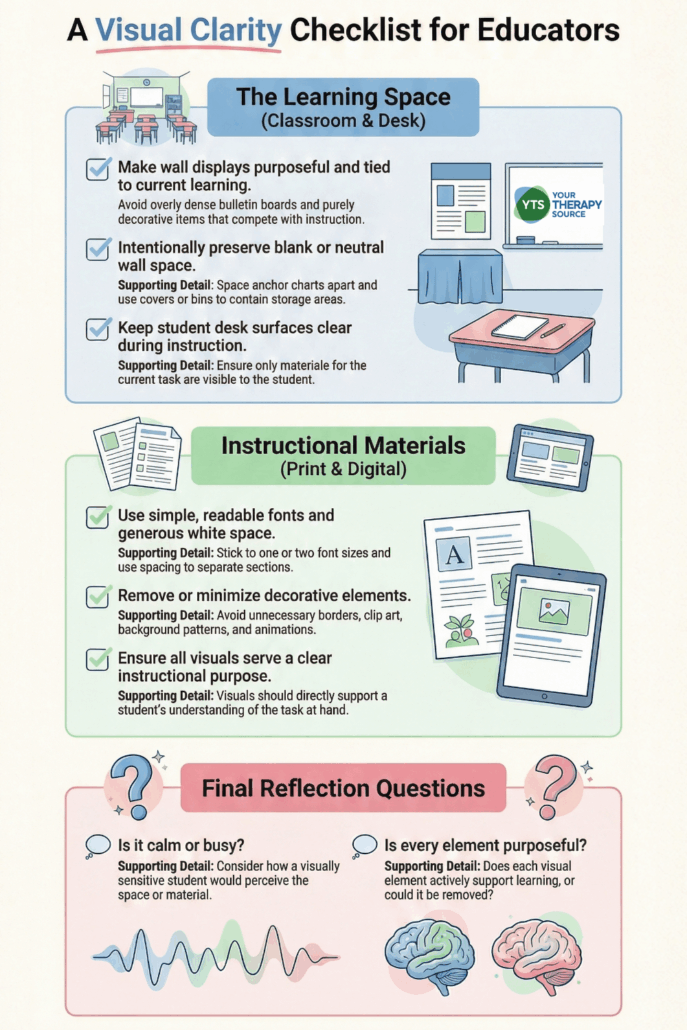

The research does not recommend specific interventions, but it highlights the importance of managing visual complexity in learning environments. One practical way to apply this understanding is by regularly reviewing classrooms and instructional materials for unnecessary visual clutter.

Educators and therapists may find it helpful to use a simple visual clutter checklist when decorating classrooms or creating worksheets. Use this checklist as a reflection tool when setting up learning spaces or designing instructional materials. The goal is to support attention, regulation, and access by reducing excess visual load.

Classroom environment check

Consider the primary learning areas from a student’s seated perspective.

- Wall displays are purposeful and connected to current learning

- Bulletin boards are not overly dense with text, images, or colors

- Visuals use a limited and consistent color palette

- Anchor charts are spaced apart rather than clustered together

- Seasonal or decorative displays do not compete with instructional visuals

- Blank or neutral wall space is intentionally preserved

- Storage areas are visually contained using bins, cabinets, or covers

- Labels are clear, readable, and limited to what students need to reference

Desk and workspace check

Review what students see and manage within their immediate work area.

- Desk surfaces are mostly clear and organized during instruction

- Only materials needed for the current task are visible

- Pencil cups, caddies, or bins are simple and not visually busy

- Visual reminders or schedules are small, consistent, and predictable

- Personal items are limited or stored out of view during work time

Worksheet and handout check

Use this section when designing or reviewing worksheets, assessments, or homework.

- Fonts are simple, readable, and consistent

- One or two font sizes are used

- Borders, clip art, or decorative graphics are minimal or removed

- Instructions are short and clearly separated from the task

- White space is used to separate sections

- Visuals directly support understanding of the task

- Multiple steps are visually broken into smaller sections

- Unnecessary icons, shading, or background patterns are avoided

Digital material check

Apply these considerations to slides, digital worksheets, and online platforms.

- Slides focus on one main idea at a time

- Text is limited and paired with adequate spacing

- Animations and transitions are used sparingly or removed

- Backgrounds are plain and high contrast

- Icons and images serve a clear instructional purpose

Final reflection

- Would this feel calm or busy to a student who notices visual details quickly?

- Is every visual element supporting learning or participation?

- Could anything be removed without reducing clarity?

Reducing visual clutter does not mean removing warmth or personality from a classroom. It means creating environments and materials that support attention, regulation, and meaningful engagement.

SUMMARY ON ANXIETY AND VISUAL PROCESSING

Trait anxiety reflects a stable pattern in how individuals experience and respond to their environment. Research on early visual processing suggests that anxiety-related differences may begin at the sensory level, shaping how visual information is experienced from the outset. In school settings, where visual demands are high, thoughtful attention to visual complexity can support regulation, access, and meaningful participation for a wide range of learners.

REFERENCES

Wu, Z., You, Y., Brown, J. A., Dolan, R. J., & Li, W. (2025). Trait-like visual cortical hyperactivity in trait anxiety. Nature Communications. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-67480-3