How Does Physical Development Affect Learning?

Most school staff are already aware of the physical benefits of exercise, such as strengthening of the heart and lungs, preventing weight gain, healthy bones, good posture and more. However, many are not aware of the potential brain-boosting benefits of physical activity with regard to school performance. How does physical development affect learning? What does the research say?

Many students are missing out on opportunities to accomplish this important physical activity. For example, years ago kindergarten was meant to teach children how to play, listen, follow rules and interact with peers. Now kindergarten teachers, and even preschools teachers, are forced to spend more time on structured, academic instruction. This frequently translates into more seatwork time and less movement and active free play time.

Physical education class and recess are usually the first things cut when more academic time is required for remediation in reading and math skills. At the end of the day, the children are spending too much time in a sedentary mode. Research indicates that this sedentary lifestyle has a negative effect on cognitive development.

How does physical development affect learning?

What is the importance of gross motor skills? Gross motor skills are completed by using the larger muscles in the body to roll, sit up, crawl, walk, run, jump, leap, hop, skip and more. Regular participation in these types of physical activities has been associated with improved academic performance and important school day functions, such as attention and memory. Even a baby’s ability to sit up unsupported has a profound effect on their ability to learn about objects (Woods, 2013).

One of the greatest brain gains of exercise is the ability for physical activity to improve actual brain function by helping nerve cells to multiply, creating more connections for learning (Cotman, 2002; Ferris, 2007). Research has shown that an increase in physical activity has a significant positive effect on cognition, especially for early elementary and middle school students (Sibley, 2002). As an added bonus, being physically fit as a child may make you smarter for longer as you grow old. (Deary, 2006).

Benefits of Gross Motor Skills and Physical Activity

Recent research indicates that regular participation in physical activity may improve academic performance. Schools that have added physical activity into their curriculum showed a 6% increase in student’s standardized test scores when compared to peers who had inactive lessons (Donnelly, 2011). One comprehensive research review included 59 studies, indicated a significant and positive effect of physical activity on children’s achievement and cognitive outcomes, with aerobic exercise having the greatest effect (Fedewa & Ahn, 2011). Ninety minutes per week of cardiorespiratory fitness has been associated with improvements in the cognitive control of working memory in preadolescent children. Children who participated in 90 minutes/week of moderate to vigorous physical activity during an after school program displayed improvements in working memory (Kamijo, 2011). Physically active lessons including physical activity breaks have been shown to reduce time-off-task (20.5%) and improve reading, math, spelling and composite scores (Kibbe, 2011). In another study, children who participated in physically active lessons had significantly greater gains in mathematics speed test, general mathematics, and spelling scores although no changes were seen in reading scores (Marijke J., 2016).

Physical education classes and recess offer opportunities for students to increase physical activity throughout the school day. Although, at times children are sedentary even during these periods. Research indicated that children who participate in physical activity during physical education lessons may facilitate immediate and delayed memory (Pesce, 2009). Many studies show that the more vigorous the physical activity is the larger the effects on academic performance (Carlson, 2008; Castelli, 2011).

Even acute bouts of physical activity have been shown to improve cognition. One study revealed that preadolescent children who completed 20 minutes of treadmill training at a moderate pace responded to test questions on reading, spelling, and arithmetic with greater accuracy and had improved reading comprehension compared to children who had been sitting. In addition, the children completed learning tasks faster and more accurately were more likely to read above their grade level following the physical activity (Hillman, 2009). Perhaps try some of these 10 easy, physically active ways to get the brain ready for testing.

How do gross motor skills/physical activity affect concentration?

Teachers know all too well how much effort is spent on trying to get and maintain students’ attention. Teachers try frequent questioning, moving about the room, changing tone of voice and many more techniques. An alternative method for teachers to increase attention, concentration and on-task behavior may be to incorporate bouts of physical activity throughout the school day. Research has shown that some children who participated in an in-class physical activity program improved their on-task behaviors by 20 percent (Mahar, 2006). Additional research regarding physical activity and school performance revealed that physical activity may improve concentration (Taras, 2005). Active lessons that require more coordinated gross motor skills such as balancing, reaction time, etc. were associated with better concentration on academic tasks (Budde, 2008).

Suggestions to increase gross motor skills/physical activity during the school day

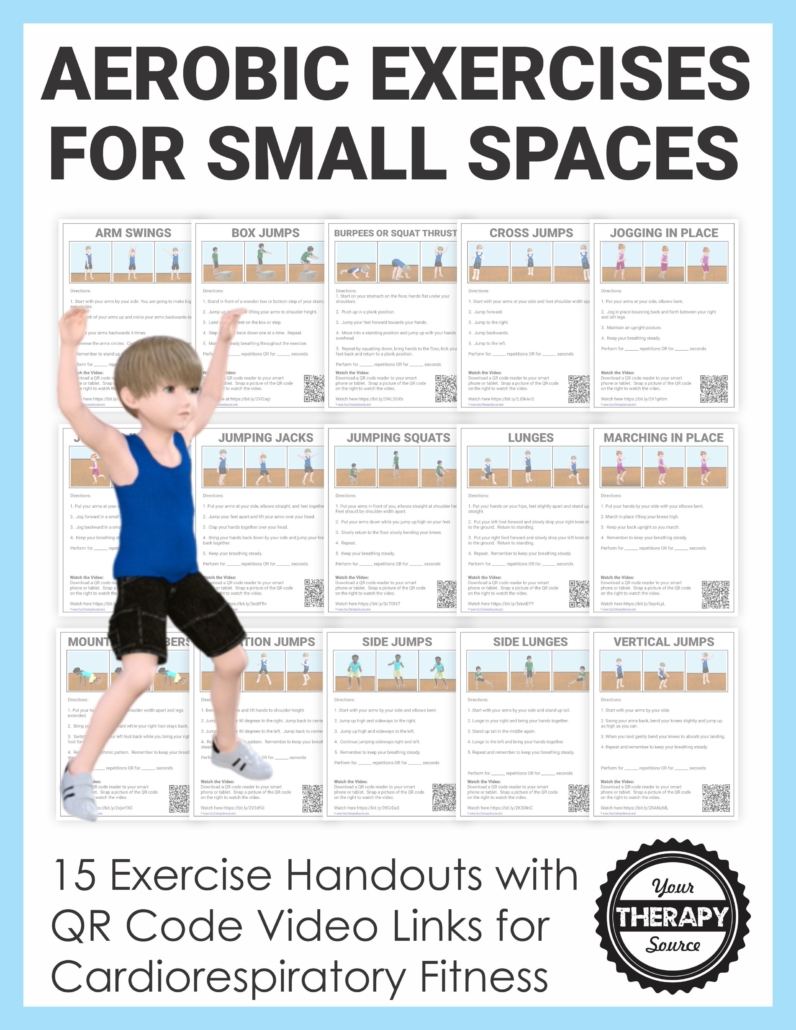

There are many ways to incorporate more physical activity and movement breaks into a school day. One of the easiest ways to increase physical activity time is to add physical education classes and recess. However, this can be the most difficult to accomplish within a school day since so much time is already devoted to structured learning. If additional physical education and recess time is not available, work on incorporating physical movement throughout the school day with brain breaks. During transitions from one subject matter to another, perform short bouts of exercises such as jumping in place, dancing to music or jumping jacks. Help teachers develop multisensory lessons that incorporate movement with academics. Not only will the multisensory activities increase movement time, but they may also assist kinesthetic learners to improve academically. By teaming up with members of the school and community, physical and occupational therapists can help make active changes to children’s patterns of physical fitness, health and cognitive function!

References:

Active Living Research (2015). Active Education: Growing Evidence on Physical Activity and Academic Performance. Retrieved from the web on 8/15/16 at http://activelivingresearch.org/sites/default/files/ALR_Brief_ActiveEducation_Jan2015.pdf

Budde H, Voelcker-Rehage C, Pietrabyk-Kendziorra S, Ribeiro P, Tidow G. (2008) Acute coordinative exercise improves attentional performance in adolescents. Neurosci Lett. 441(2):219–223.

Carlson SA, Fulton JE, Lee SM, et al. (2008) Physical education and academic achievement in elementary school: Data from early childhood longitudinal study. Am J Public Health. 98(4):721-727. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2007.117176.

Castelli DM, Hillman CH, Hirsch J, Hirsch A, Drollette E. (2011) FIT Kids: time in target heart zone and cognitive performance. Prev Med. 52(Suppl 1):S55-S59

Cotman, C., & Engesser-Cesar, C. (2002). Exercise enhances and protects brain function. Exercise and Sport Science Review, 30(2), 75-79.

Deary, I., Whalley, L., et al. (2006). Physical fitness and lifetime cognitive change. Neurology, 67, 1195-1200.

Donnelly JE, Lambourne K. (2011) Classroom-based physical activity, cognition, and academic achievement. Prev Med. 52 (Suppl 1):S36-S42.

Fedewa AL & Ahn S. (2011) The effects of physical activity and physical fitness on children’s achievement and cognitive outcomes: a meta-analysis.

Res Q Exerc Sport. 82(3):521-535.

Ferris, L., Williams, J., & Shen, C. (2007). The effect of acute exercise on serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels and cognitive function. Medical Science of Sports and Exercise, 39(4), 728-734.

Hillman CH, Pontifex MB, Raine LB, Castelli DM, Hall EE, Kramer AF. (2009). The effect of acute treadmill walking on cognitive control and academic achievement in preadolescent children. Neuroscience. 159(3):1044-1054. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.01.057.

Kamijo K, Pontifex MB, O’Leary KC, et al. (2011). The effects of an afterschool physical activity program on working memory in preadolescent children. Dev Sci. 14(5):1046-1058. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7687.2011.01054.x

Kibbe Dl, Hackett J, Hurley M, et al. (2011) Ten years of TAKE 10!: integrating physical activity with academic concepts in elementary school classrooms. Prev Med.52(Suppl 1):S43-S50.

Mahar, M., Murphy, S., Rowe, D., et al. (2006). Effects of a classroom-based program on physical activity and on-task behavior. Medical Science of Sports and Exercise, 38(12), 2086-2094.

Marijke J. et al (2016). Physically Active Math and Language Lessons Improve Academic Achievement: A Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial. Pediatrics, Mar 24;137(3):e20152743. Epub 2016 Feb 24.

Pesce et al (2009) Physical activity and mental performance in preadolescents: effects of acute exercise on free-recall memory. Ment Health Phys Act. 2(1):16–22.

Sibley, B., & Etnier, J. (2002). The effects of physical activity on cognition in children: A meta anaylsis. Medical Science of Sports and Exercise, 4(5), 214.

Taras, H. (2005). Physical activity and student performance at school. Journal of School Health, 75(6), 214-218.

Woods RJ & Wilcox T. (2013). Posture support improves object individuation in infants. Dev Psychol. Aug;49(8):1413-24. doi: 10.1037/a0030344. Epub 2012 Oct 8.

Comments are closed.